BY DOMINIC PINO, STAFF WRITER

If you’ve ever taken a history class, you know history is complicated. The lines between good and evil are rarely as clear as we want them to be, and many of our heroes had tremendous faults. This goes for all of history, from Martin Luther, who wrote some despicable and vile things about Jews, to Martin Luther King, Jr., who cheated on his wife — a lot.

It also goes for George Mason, who owned enslaved people.

The Virginia planter and namesake of our university owned around 100 people throughout his lifetime, which was abnormally high for the time. His Gunston Hall plantation would have been unsustainable without slave labor running household affairs and agricultural production. He purchased children as young as 8 years old. He was a knowing and willing participant in one of the most horrific systems of oppression that humans have yet conceived.

Mason also wrote the Virginia Declaration of Rights in May 1776, which would influence the Declaration of Independence two months later, the Bill of Rights fifteen years later and the founders of West Virginia almost one hundred years later. Mason was also a very active participant at the Constitutional Convention, but ultimately refused to sign the Constitution. He listed sixteen reasons for his refusal to sign. One of those reasons being: “The general legislature is restrained from prohibiting the further importation of slaves for twenty odd years; though such importations render the United States weaker, more vulnerable, and less capable of defense.”

That’s right, one of the reasons Mason — who owned around 100 slaves — refused to sign the Constitution was because it didn’t allow Congress to end the slave trade fast enough. Was Mason the worst kind of hypocrite? Or was he a good man tormented by his conscience? The truth is probably somewhere between those two extremes.

Our namesake holds a complicated legacy, and that puts the university in a tough spot. We’ve got a larger-than-life statue of the guy at the center of our campus, greeting visitors and providing a focal point for student life. Is that right?

The university has worked hard to answer that extremely challenging question. As part of the Campus Core project, they have unveiled a redesign of Roger Wilkins Plaza (commonly known as North Plaza) that features a new memorial to the enslaved people of George Mason. The memorial is equal parts artistic, just and welcome.

The memorial features the work of the Enslaved Children of George Mason project, led by history and art history professors Wendi Manuel-Scott and Benedict Carton, with help from five student research assistants working with an OSCAR grant. They compiled an impressive amount of information on the history of Mason’s slaveholding — all of which is easily accessible on the project’s website.

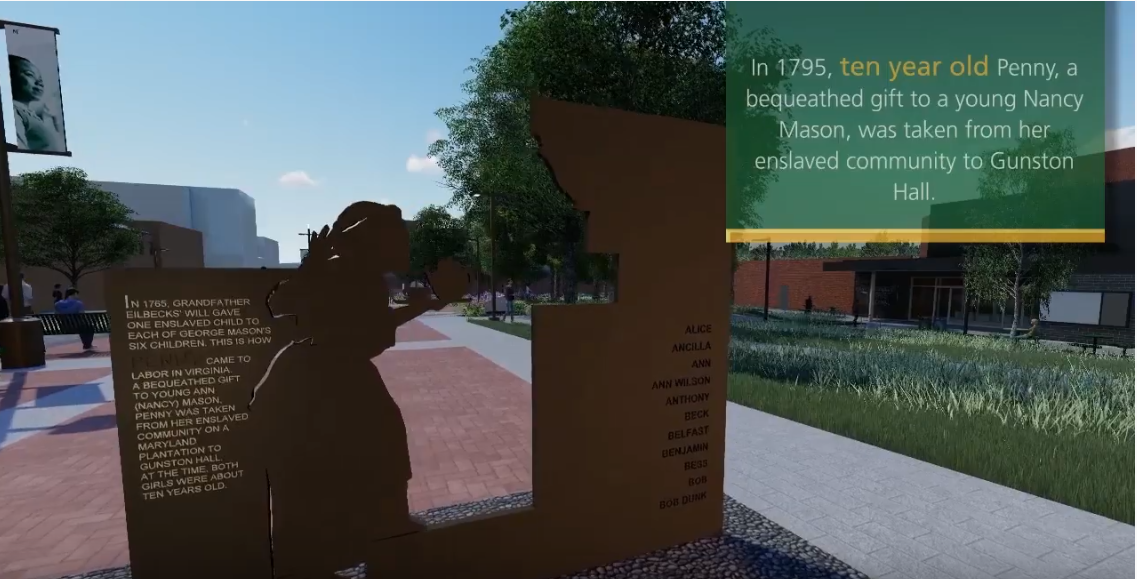

Finding information on people deemed subhuman by the society in which they lived is next to impossible, but the research team was able to find an inordinate amount of information on two enslaved people, Penny and James. Penny was a 10-year-old girl who would have done household chores. James was Mason’s personal attendant and had much authority over Mason’s residence.

The fruits of that research project will be prominently displayed in the new Wilkins Plaza, with Penny and James’ personal stories being shared with the world for the first time, along with the names of all of Mason’s slaves for whom records exist. A silhouette of Penny depicts her doing one of the tasks she was forced to do, serving tea. A silhouette of James depicts him writing with a quill pen, standing tall. James’ silhouette features a striking quote from Roger Wilkins: “They did not just endure: they lived and created and passed down strength and power and hope and love.”

The ingenious part of the memorial is how the designers play with lines of sight. There will be a spot where you can stand and see Penny’s silhouette line up with the Mason statue. It’s honest about the oppression of slavery, admirably avoiding sugarcoating a difficult issue. The spot where you stand will include this injunction: “Consider how slavery and freedom coexisted in America.” Finally taking that question seriously is vital to understanding the past and creating a better future.

The spot where James’ silhouette lines up with the Mason statue presents a different injunction: “Consider how rights have changed since Mason’s time.” Nowadays, we would all give James the credit for the success of Gunston Hall since he actually did the work, but Mason unjustly got the credit in the 1700s.

The memorial is a beautiful display of balance. It balances Mason’s preeminence with his flaws. It balances the oppressive and cruel past of slavery with a sober and hopeful look to the future. It balances students and faculty and administrators. And it balances, at least in part, our view of history as Mason Patriots.

Everyone would be wise to read up on the plans for the memorial, and the university has provided copious amounts of material to read and watch. You’ll learn something new and appreciate the work that was put into the project.

If you’re going to criticize the project, don’t do it from a place of ignorance like the Resident Student Association (RSA) did in an open letter to President Holton on the subject. The letter states, “The Association’s fear is that individuals coming to the university will miss the intent of the memorials being a conversation starter and a place to reflect, but rather will see them as being a means of the university glorifying the fact of George Mason IV owning slaves.” Leaving open the possibility that anyone at this university is glorifying Mason’s slaveholding is grotesque and demonstrates a clear failure to even attempt to understand the purpose of the memorial. RSA did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

Student Body President Camden Layton quote-tweeted RSA’s letter with “lol what.”

In an email to me, he said, “I absolutely love this memorial … After hearing from Dr. Wendi N. Manuel-Scott at the Board of Visitors meeting last spring in regards to this, I was absolutely blown away by the thought and attention that went into this. Honestly, the concept of this coming out of a student research project just goes to show Mason’s commitment to not only the subject of the memorial, but also to our commitment to education and research.” He added that he can’t wait to come back after graduation and see it in real life.

Neither can I. History is complicated, and Mason has come up with a beautifully balanced memorial on an incredibly difficult subject. The university’s behavior on this issue should serve as a model to other organizations presented with challenging questions. Nothing can ever make slavery right or erase George Mason’s flaws. His memorial does not attempt to do either of those things — and for that it deserves our applause.