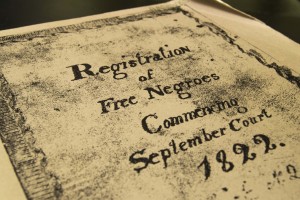

This book was used to record details of free men in case their identities were doubted. It includes names, origins and physical descriptions, among other characteristics. (Alya Nowilaty/Fourth Estate)

Georgia Brown, an undergraduate history major, is working with the Fairfax County Historic Records Center to create a searchable index of slaves mentioned in court documents.

Brown, along with the other historians in the office, searches through documents like wills, inventories, deeds and estate accounts, looking to find any mention of slaves: who owned them, who they were sold to or even if they were emancipated.

Brown started the project when she began her internship with the Historic Records Center in January. The center had a few projects that the interns could choose from and Brown chose to work on the slave index.

“I chose this project because I love finding people in historical records that are either lesser known or unknown,” Brown said. “Of course, we have some big names in our records, but the wills I enjoyed reading were from those who had maybe one horse or one bed to give away in the end.”

Early in the endeavor, Brown said that she and historians at the center were not sure what they would find or even how they would note down and compile the information.

“I didn’t know if [the slaves] would even be named,” she said. “But as we’re going along, I’m seeing a lot of them have names and a lot of them have last names. We had African names also, names like Mohammad and Anya, Arya, Cato and Sambol.”

By the time they had searched through half the records, Brown and the other historians decided to find a way to compile the information into a searchable database. When they found out that the online infrastructure for a slave index did not exist, they created their own index with three-by-five index cards and filing cabinets.

“Now we’re going through, and each time there is a slave’s name we make a card for the slave owner, and then we list everyone who was in [the document],” Brown said. Each slave also gets his or her own card, filled with as much information as the historians can find. The cards are organized in the filing cabinet by name, and whether the individual was a slave, slave owner or a freed black.

One example was Henry Zimmerman, who had three slaves: Hannah, Winn and Nate. A card was made for Zimmerman and then three separate cards were made for his slaves. The information on the cards reveals a lot about the individuals, but there are many holes. For example, Hannah had a list value of 50 cents, which indicates her older age, according to Brown. The estate account did not list to whom the slaves were sold after Zimmerman’s death, so Brown has not found any additional information about the lives of Hannah, Winn and Nate. Still, she is hoping that some mention of them will appear in later records.

Heather Bollinger, an archivist who works with Brown, said that although most of the mentions of slaves in court records occur in relation to their owners, they would sometimes make appearances in relation to emancipations.

An example Bollinger gave was about a man named Whiting Mills who indicated in his will that after his death, his slaves should be freed either at the death of his wife or in the case that she remarried. His wife, Ruth, did remarry, and the slaves showed up at court with a lawyer sometime between 1810 and 1815 to sue for their freedom.

The Fairfax County Historic Records Center houses court documents that date from the formation of the county in 1742 until the early 1900s. Mason student Georgia Brown is working with local historians to search through all of the center’s documents in order to create a comprehensive index of slaves. (Alya Nowilaty/Fourth Estate)

Brown has studied over 120 years of wills in one semester and hopes to finish the index before she completes her internship in May. Although the entire records center is lined with bookshelves and boxes containing historic probate records, Bollinger said that many records were also lost during the Civil War. Going through the documents to compile the index, Brown said, is like a really good story she would like to keep reading until the end.

“The fact that we now have 10,000 previously unnamed people indexed and searchable makes me extremely proud of what we’re doing,” Brown said. “We’re giving a voice to those who were stifled for one hundred and twenty years in this county. That’s definitely enough motivation for me to see this project through to the end.”

Virginia slavery and the founding fathers

By 1749, 28 percent of Fairfax County’s population was composed of slaves, according to “A Brief History of Fairfax County” published by county historian Donald M. Sweig in 1995. By 1782, that percentage had increased to 41 percent.

The first slaves who came to Virginia arrived in Jamestown, and some historians argue that the first Africans to arrive were indentured servants from an Iberian ship, said Spencer Crew, a Clarence Robinson professor at Mason. It was not until midway through the seventeenth century, at which point the status of African workers changed from indentured servitude to enslavement, that the British began to take control of the slave trade.

“As more individuals were brought to Virginia, [the settlers] needed a permanent labor source. The Native Indians were not working out for a variety of reasons. One is that they knew the land so they could run away and disappear, and another is that they were being harmed by the diseases that were brought [by the Europeans],” Crew explained.

When Virginia changed its agricultural system and cash crop from tobacco to grains, the demand for slave labor in the Commonwealth decreased, as the soil was left depleted from the tobacco. To continue making profit, Virginia slave owners started to export their slaves to southern states that grew cotton, like Alabama and Mississippi. According to Sweig, as many as 5,000 slaves were sold and shipped down south.

“Something to keep in mind is that the value of enslaved people in this country in the nineteenth century was higher than the value of all the industry, all the maritime activity and all the financial institutions combined,” Crew said. “They were a very important commodity.”

Although Virginia did not have the expansive cotton plantations of the Deep South, plantations like Monticello, Montpelier, Mount Vernon and Gunston Hall did exist and are remembered today because of their prolific owners: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, George Washington and George Mason, respectively. These Virginians were founding fathers, future presidents and slave owners.

“They’re not perfect,” Crew said about the founding fathers. “I don’t believe that the founding fathers are perfect and should be put on pedestals. I see them as human beings who have weaknesses and strengths. It is a very useful way to view and understand them, to understand the country and to understand that from the very beginning the issues of slavery and race are sort of central to conflict and discussion to our nation.”

The wills of two of our founding fathers, George Mason and George Washington, can be found in the Fairfax Historic Records Center and illustrate that conflict.

“We have all the good ones!” joked Brown about the documents. “We have George Washington’s will and his wife’s. In his will, he actually only freed one slave. The other ones went to his wife until she died, but she had her own slaves from her first marriage, and she never frees her slaves. She gives them to her kids.”

Gunston Hall was home to founding father George Mason. Even though Mason questioned the morality of slavery, he never freed his own slaves and instead left them to his children. (Amy Rose/Fourth Estate)

George Mason had a different story. According to Crew and Gunston Hall’s website, Mason indicated in some of his publications, including speeches given at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, that although he was not willing to abolish the practice of slavery, he did question the morality of the business.

“He’s struggling with it in his own mind’s eye, as opposed to some people who think, ‘It’s just the way it is, it’s fine, I need them,’” Crew explained.

In his will, however, Mason chose not to emancipate his slaves, instead bequeathing them to his children. An example: “To my eldest Daughter Ann the four Following Slaves and their increase. To wit, Bess (the Daughter of Cloe) and her child Frank, mulatto Priss (the Daughter of Jenny) and Nell (the Daughter of Occoquan Nell) [sic].”

At Mason, a different reality exists. Crew said he is often struck by how outwardly repelled students are by the concept of slavery.

“I find it gratifying that there’s a real sense of ‘this is wrong,’ and it makes me feel like I got hope for the next generation,” Crew said emotionally, followed by a chuckle.

Solving ancestral mysteries

Chanel James, a junior graphic design major, said she knows her family has slave roots, but they have trouble tracing their ancestral line.

“My great grandparents were sharecroppers, which is when freed slaves were given land and a little bit of money. All the money they would make from that land would be given back to the [landlord], so basically it was still slavery,” James said.

Her family relies on passing down its history orally, but sometimes obstacles, such as losing tapes with recorded stories or the death of an older family member, can create ancestral mysteries.

Coming to Mason from Richmond and seeing the diversity of Northern Virginia sparked an interest in James to search for her roots.

“Before I came here, I really didn’t tell my story. I just said that my family is probably from Africa, because you feel bad thinking your family were just slaves. Now I think it is a cool history,” she said. James took an African American history class last semester to learn more about her past. She now wonders if her African ancestors were shipped to other countries, such as Caribbean states with sugar plantations, before ending up in the United States.

Brown hopes that the slave index she is working on will make it easier for African Americans to trace their families and find their ancestors.

“Before, it would have been like finding a needle in a haystack,” she said. “[The index] is linking them together, so we can find them now, trace them from dad passing them on to his son or daughter.”

For Crew, tracing African American family history is personal to him, as he said he and his family have started doing their own family research. The historical society located in his family’s town in South Carolina had a publication that compiled every single mention of African Americans in the local newspaper, which helped him discover more about his family members.

For James, whose family is not native to Virginia, the index provides her with the ability to learn more about the lives of slaves.

“In school, when you learned about slavery, you always heard about the negative consequences and the majority. You didn’t hear about the individuals. So even if I were to go through the Fairfax index, even if I were to look at individuals who aren’t related to me, I think I would like that. It would be cool,” she said.

With a family reunion approaching this summer, James is excited to continue gathering her family history from her older relatives, some of whom she has never even met before. Hearing about Brown’s project also inspired her to check out the local historic centers around her family’s hometowns to expand her search.

“Being younger, I would have approached [my family history] being ashamed. Growing up in a majority black community, everyone was everything but black. No one wants to admit that they’re black or African American,” James said, laughing about how people like to talk about their German or Native American ancestry instead of discussing their black roots. “Now, I find it more empowering because of the fact that it is a topic that no one wants to talk about. It is like you’re a survivor; a lot of people died on the slave ships, but the one person who survived is why I am here.”