BY DOMINIC PINO, STAFF WRITER

One of the foremost challenges college students face is inexperience. We’re nervous about the sparse experience section on our resumes when we apply for jobs. We’re nervous about our inexperience with relationships. We’re nervous about sounding stupid because of intellectual inexperience. We’re young, and we haven’t done what older people have done, experienced what older people have experienced or learned what older people have learned.

So what can we do to fill those gaps in our experience? We can talk to people who have experience. Parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, professors, clergy, friends and coworkers are all resources available to us with more experience in various ways.

Talking to those more experienced people is a choice, however. We can always choose to wallow on our own and whine about why everything is unfair and everyone is out to get us. We’ve all been there from time to time, but after gathering ourselves and talking to someone else, we often look back and think to ourselves, “What was I so worried about?”

I think this is partly what the writer of Ecclesiastes meant when he wrote, “What has been will be again / what has been done will be done again / there is nothing new under the sun.” You think your situation is unique? It’s not. It’s happened before.

If you’re civically engaged — and you should be if you’re not — then similar rules apply. It’s tempting to look around and think the government is in irreparable chaos, the Constitution is done for, and we’re in uncharted territory.

There’s nothing new under the sun.

If you think the government is chaotic now, imagine what it was like when people were arguing over whether it should even exist. You want to talk about chaos? Try writing a letter to the king of the most powerful country on earth that basically says, “Excuse me, we don’t belong to you anymore.”

Try having that king respond, “That’s cute,” and send his armies to fight a war against you.

Try shocking the world by winning that war, and then saying, “OK, that was great, but what are we going to do now?”

Try failing in your first attempt to create a brand new government from scratch (it’s hard), and having everyone get antsy about whether this whole thing is going to work at all, so you try again, but this time there are clearly-defined sides for and against the new constitution you just wrote.

Try convincing people who sincerely believe you want to trample their rights and take their money to agree to a whole new form of government.

Try doing all of that in less than 20 years.

In short, try founding a country.

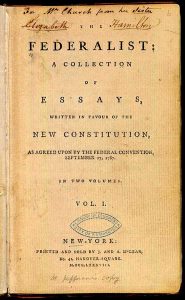

That’s what the framers of the Constitution were doing and they made their case to the nation in the Federalist Papers. There are 85 Federalist Papers, and if something is in the Constitution, there’s a Federalist Paper that mentions it. A majority were written by Alexander Hamilton (you know, from the musical), a big chunk are by James Madison (a superior intellect despite his inferior namesake university), and a few are by John Jay (yes, that’s his entire name).

We can learn from their experience today. If you’ve ever taken a government class, you’ve read Federalist No. 10 and Federalist No. 51, Madison’s two clearest expositions of what American government is all about, but there is so much more. You can read Federalist No. 68, about the electoral college, and discover that it was actually the least controversial part of the Constitution. You can read Federalist Nos. 12, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 and 36, about taxation, and see why they found that topic important enough to devote eight papers to it. You can read Federalist No. 39, about the “republican form” of government, to understand what Madison means by that phrase. You can read Federalist Nos. 65 and 66, about impeachment, for no reason in particular.

The Federalist Papers provide not only good information about our government but also a model for how to argue in public. They were originally published in New York newspapers for the public to read. Hamilton, Madison and Jay went after the Anti-Federalists pretty hard in some spots (especially in Federalist No. 26), but they always treated them with respect and never attacked them personally. Politicians nowadays could learn a thing or two from them. If inventing America wasn’t worth personal attacks, then representing a congressional district for two years certainly isn’t.

While the Federalist Papers aren’t always easy to read, they are conveniently split up into bite-size parts since they were originally newspaper articles. Better yet, they are all available for free on Congress’ website, although I would recommend a nice bound copy. I have the Signet Classics edition, which includes helpful reference material, bullet-point summaries of each paper, and copies of the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation.

The Federalist Papers aren’t a secret decoder ring for the Constitution, and they don’t have answers to all our questions. But it would be foolish to not lean on them as repositories of American experience. Just as college students are inexperienced and need help from older people, our present political situation needs help from the experience of the past. The Federalist Papers are a good place to start.