World debut of “What Problem?” performance closes out Artist-In-Residence at the CFA

BY NAYOMI SANTOS, ASSISTANT CULTURE EDITOR

In its second installation, the Center for the Arts’s (CFA) Artist-in-Residence program continues to foster the collaboration between world-renowned artists and Mason community members.

“We started the Mason Artist-in-Residence program this year, with the goal of increasing the amount of time that the artists are in our community,” said CFA Director of Programming Adrienne Bryant Godwin, “in order to foster opportunities to have truly meaningful exchange between artists and between community members.”

During the week of Jan. 27, the CFA hosted the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company as the year’s first Artist-in-Residence. Bill T. Jones and members of the company — which was founded in 1982 by Jones and the late Arnie Zane — taught and collaborated with both Mason and Fairfax community members. By conducting masterclasses and workshops, members of the company offered their expertise in the world of dance.

Jones is currently the Artistic Director and Choreographer of Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, and the Artistic Director of New York Live Arts.

In addition to the masterclasses, the program also hosted a town hall on Wednesday, Jan. 29, with Jones alongside Mason School of Integrative Studies professor Wendi N. Manuel-Scott and Franklin Dukes, a mediator with the Institute for Engagement & Negotiation at the University of Virginia in the Historic Town Hall of Fairfax.

The program’s town hall portion is one of the unique instances where the community can directly interact with the Artist-in-Residence. In this case, community members discussed their own experiences and thoughts on the concept of identity with Jones, Manuel-Scott and Dukes, while asking some pretty hard questions.

After giving a brief biography of the speakers, including herself, Manuel-Scott gave the room a prompt to think about. “Tell us something about your biography that was particularly meaningful,” she said, “and that was shaped by a myth, a mythology, and how have you evolved from or started to disrupt that mythology in your own biography.”

Jones began by talking about growing up in a segregated neighborhood during the civil rights movement, and how the “free love” crusade of the ‘70s influenced him and his community and how that all plays into mythology.

When thinking about myths, Jones discussed one statement that is largely mentioned in talks regarding social justice: the Martin Luther King Jr. quote, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

“I’m finding more and more these days, I’m saying ‘I don’t know if I believe it,’” he said. “And that’s a really painful thing to say.”

Dukes also offered his take on this “myth.” “I think the moral arc of the universe bends the way we make it bend. I think cynicism is complicity and apathy is complicity,” he said.

One prompt that Jones offered dominated the rest of the town hall. “Why should a person care to make a better world?” he asked. Especially when that someone has everything they need, why should they care? And if they don’t, are they the problem?”

Several community members ranging from high school students to Mason students to residents of the area all took a shot at answering the prompt. Some offered their own ways of contributing to making the world a better place.

For instance, J. Bouey, a dancer with the company, talked about how important it is to care because we are all connected. “Where you get your money from is connected to the [prison] industrial complex,” Bouey said. We can make direct connections to everyone in this room.”

Dance major Carmella Taitt offered a different perspective on why it is essential that we care for each other. “It isn’t the future, but it’s the past,” Taitt said. “That is the reason that we should be motivated to reach freedom for ourselves and for each other.”

Finally, one audience member, a veteran named Troy, concluded the town hall with another prompt. “You don’t have to [care], not only do you not have to, it’s okay if you don’t, as long as you’re willing to accept the consequences,” he said. “In the affirmative that [Jones] asked the question, maybe the answer is in the negative: What happens to a society when you don’t [care]?”

Though the town hall wasn’t focused on the CFA’s world debut of the show “What Problem?” on Saturday, Feb. 1, the same prompts and issues raised during the night appeared in the performance. The movements of the dancers along with intermittent singing — at times from the dancers themselves — attest to the continuous questioning.

This was purposeful. According to Janet Wong, the associate artistic D]director of the company, Jones decided to have the town hall to spark even more conversation and thought that went beyond the show.

“We didn’t want the conversation to begin and end with the performance,” Wong said. “We believe that the piece can trigger and inspire conversations, even before [the audience] sees the show and, hopefully, after they’ve seen it.”

Wong also offered some context for the piece and what inspired its creation. At the center is the character Pip, from Herman Melville’s classic “Moby Dick.” Pip, a young Black cabin boy who jumps ship when the whale bumps the boat and is left to drown by his shipmates, is the beginning of the journey that Jones and the dancers take the audience on. Melville’s writing of Pip’s fate plays a pivotal role in the piece. Jones was also inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech as well as the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois, which prompted the title of the piece.

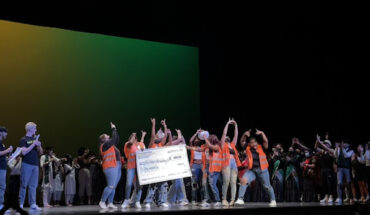

The show is essentially divided into three sections. Beginning with one — Jones — then one plus 10 as the company joins Jones and concluding with Jones, the company and 22 Mason and Fairfax community members on stage. In its impactful conclusion, each dancer gave one sentence that describes them, their identity or community.

The inclusion of 29 Mason singers also contributed to the sense of community and collaboration that is critical to the piece.

Prior to the show, Wong hinted at the question that the piece attempts to answer. “This idea of the ‘we,’” she said, “the pursuit of the ‘we.’ Is there such thing as a ‘we?’”

At the end of the 90-minute show, it is up to the audience and individual to decide.