College of Education and Human Development works to increase educators proficient in braille and visual impairment accommodation

BY ALEXA TIRONI, ASSISTANT NEWS EDITOR

Lilley Fitzgerald was born with Stargardt macular dystrophy, an inherited disorder of the retina that results in progressive vision loss during childhood and adolescence. As the only visually impaired (VI) student in her district, Fitzgerald could have been left to slip through the educational cracks, as many VI students do, had it not been for the dedicated teachers around her.

“I would say they did the best job with what they had … I mean, anything I needed all my teachers would help,” Fitzgerald said. “We would have one on one talks about what I needed, what was working, what was not working — which really helped me figure out that I have a voice and can stand up for that.”

She had access to assistive technology like Closed Circuit Television, which she used to enlarge texts to make reading easier and mathematical equations more comprehensive.

However, not all VI persons have the same early educational experiences. Kimberly Avila, the Mason professor in charge of the preparatory program for working with visually impaired and blind students, experienced the frustrations from a lack of accessibility.

“I’m visually impaired and I didn’t get much help at all in school and so I grew up thinking that I had — my challenges with reading were because of something else, but really it was because the print was just too small,” Avila said.

She continued, “I didn’t have access to braille and so I didn’t do very well in school, but when I went to college I met up with an organization that introduced me to all these technologies and devices, and literally that semester I had access to those my GPA went to almost a 4.0 and I just felt much more confident in learning.”

Avila currently works as the coordinator to the Virginia Consortium for Teacher Preparation in Vision Impairment, and described the lack of specialized teachers in the field as a “chronic problem.”

The consortium is the only academic program preparing teachers for students with visual impairments in the state, and is made up of five universities: George Mason University, James Madison University, Norfolk State University, Old Dominion University and Radford University.

There are several degrees available through the VI program. A student can pursue a bachelor’s or a master’s degree with a concentration in VI, an undergraduate minor or a graduate certificate.

“All the instruction is taught through George Mason, so it’s a really neat collaboration because our partner universities have contacts in their part of the state that I don’t, and so I really rely on this as how we can reach people,” Avila said.

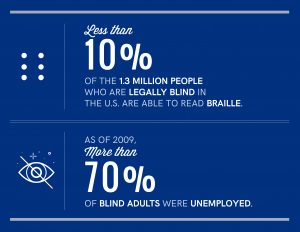

The program, however, is about more than just teaching braille literacy — it’s about creating equal access and opportunity. According to a 2009 report written by the National Federation of the Blind (NFB), less than 10 percent of legally blind people in the U.S. can read braille.

The inability to read braille is more than just a communication inhibitor — it can greatly impact a visually impaired or blind person’s likelihood of finding employment. In 2016 the NFB reported a 70-75 percent unemployment rate within the community and that 27.7 percent were living below the poverty line.

Pamela Baker, associate professor and division director of Mason’s Special Education and disAbility Research, spoke on the lack of proper opportunities and braille education, saying, “There are places that don’t have access to people who are trained and who can teach in that area. There is also that assumption that if you can hear it you can be able to read, and when you look at employment opportunities that’s where the breakdown occurs.”

“In the workplace, you have to be able to read and write in the vast majority of positions, and braille is just reading with your fingers,” Baker said. “But, the idea being that if we don’t prepare people to do that, we limit their independence.”

Avila reported research of her own in regards to VI people in the workplace. “It has to do a lot with accessibility,” she said. “So, if we have employers that have inaccessible platforms and digital systems that they use, then that’s going to create a barrier.”

She continued, “I also think there are barriers in employers seeing a person who is visually impaired as being a valuable asset to their work environment.”

Avila works as an advocate for equity in the workplace for visually impaired and blind persons. When companies and agencies acquire assistive technology such as screen readers and braille displays that generate refreshable sentences to correspond with the words on screen, they create a more inclusive workplace.

Fitzgerald is now pursuing her master’s in special education with a concentration in VI. “Just having that experience of being someone who is visually impaired, I really felt like I could relate with my students,” Fitzgerald said.

She spoke of her passion for the field and the necessity of educators, saying, “I think it kind of boils down to the students; they need specific help, they need specialized help with braille and adapting worksheets, and different things so they can have the best education.”

“I want to help them the way that I was helped … I want someone to have that experience, and be able to come out on the other end and be like, wow, I did it,” Fitzgerald explained.