Problems with on-campus housing continue into 2019

BY IZZ LAMAGDELEINE, COPY CHIEF

After senior communication major Madeline Powell applied for on-campus housing last year, she received an email from the department responsible for accommodating the “more than 6,500 current Mason residents and staff that call Mason home,” according to its website.

The email contained an update from Housing: they were not guaranteeing her or anyone else who had 70 credits and above space on-campus the following academic year.

“[From] there on, most seniors dropped off the waitlist and decided to go off-campus,” Powell said. “Me, I stayed on the waitlist while looking for off-campus housing. And the two groups that I had for off-campus housing didn’t work, and then I was like, ‘Okay well, guess I’m on my own,’ and because I stayed on the waitlist that’s why I come (sic) to the triple.”

She was placed in a forced triple in Piedmont, a room that has three students living in it that was initially designed for two. Powell lived with two other sophomore girls who already knew each other before living together, whom she described as “awesome” and “great” girls.

However, as the room was meant for one less student, more thought had to be put into how it was going to work for all three to live there.

“In terms of organization and space, it took us a minute to figure it out, because I had to get bedraisers to put my own fridge underneath the bed and then they had their own fridge together,” Powell said. “And then there’s no third closet, so … we literally stacked the wardrobe on top of the dresser.”

The three made the best of the situation, and Powell considered the forced triple “not that bad,” but also said that it felt cramped. “At times you feel like you couldn’t breathe, but there was a lot of stuff in the room,” she said.

Powell also felt like her situation was not as bad as other students’ have been because she and her roommates communicated with each other. However, by November she had moved out of her current dorm, and is now living in Tidewater in a single space with a kitchen attached.

In addition to living in a smaller space than expected during part of the school year, Mason put Powell on the waitlist until July, leaving her uncertain about where she was going to live until a month before classes began in late August.

In addition to living in a smaller space than expected during part of the school year, Mason put Powell on the waitlist until July, leaving her uncertain about where she was going to live until a month before classes began in late August.

“I was going to find either an apartment at Camden [Fairfax Corner Apartments and Fair Lakes Apartments] or anything near closer to the campus,” Powell stated.

However, Powell does not have a car, meaning she would either have to find a place to live that was accessible to public transportation or get a car so she could commute from campus to where she was going to live.

Further complicating her situation was that Powell and her family had just moved from Centerville to Bristow, a distance that she estimated increased her potential commute by 25 minutes. “It’s not as convenient, considering what I do on campus and how I’m involved on campus,” she said.

Powell’s situation illustrates a choice that many students at Mason have to make: deciding whether living on-campus or off-campus past their freshman year at Mason is the best option for them.

However, availability could limit the amount of students who can live on-campus. Freshmen and sophomores that have come straight to Mason from high school are all guaranteed on-campus housing. Upperclassmen and transfer students are not.

An email about the housing process sent by Housing on Jan. 24 read, “All residents have the opportunity to apply for housing for next year. All current residents who will be freshmen or sophomores next year are guaranteed the opportunity to select housing.”

It continued, “The intent of the policy is to give first time college students at Mason at least four continuous fall and spring semesters to live on-campus. The number of upper-class students able to select housing for next year will ultimately depend on the level of demand from students who are guaranteed housing.”

Furthermore, the cheat sheet for last year’s housing process states that any student that lives on campus next year needs to be a “current on-campus resident who will have lived on campus for six or fewer semesters at the end of Spring 2018.” The cheat sheet for the upcoming housing process has not been posted yet.

The limitations of where upperclassmen can live is another issue that can harm their chances of living on-campus the next semester.

“Always … we have a very finite number of rooms,” Melissa Garza Thierry, then-associate director of housing services, said. “We just can’t build wherever we want to … Every year, since we don’t require students to live on-campus past their freshman year, we never know how many students are actually going to apply to live on-campus. That’s the big unknown.” Thierry is now the associate director of regional campuses for university life at the Arlington campus.

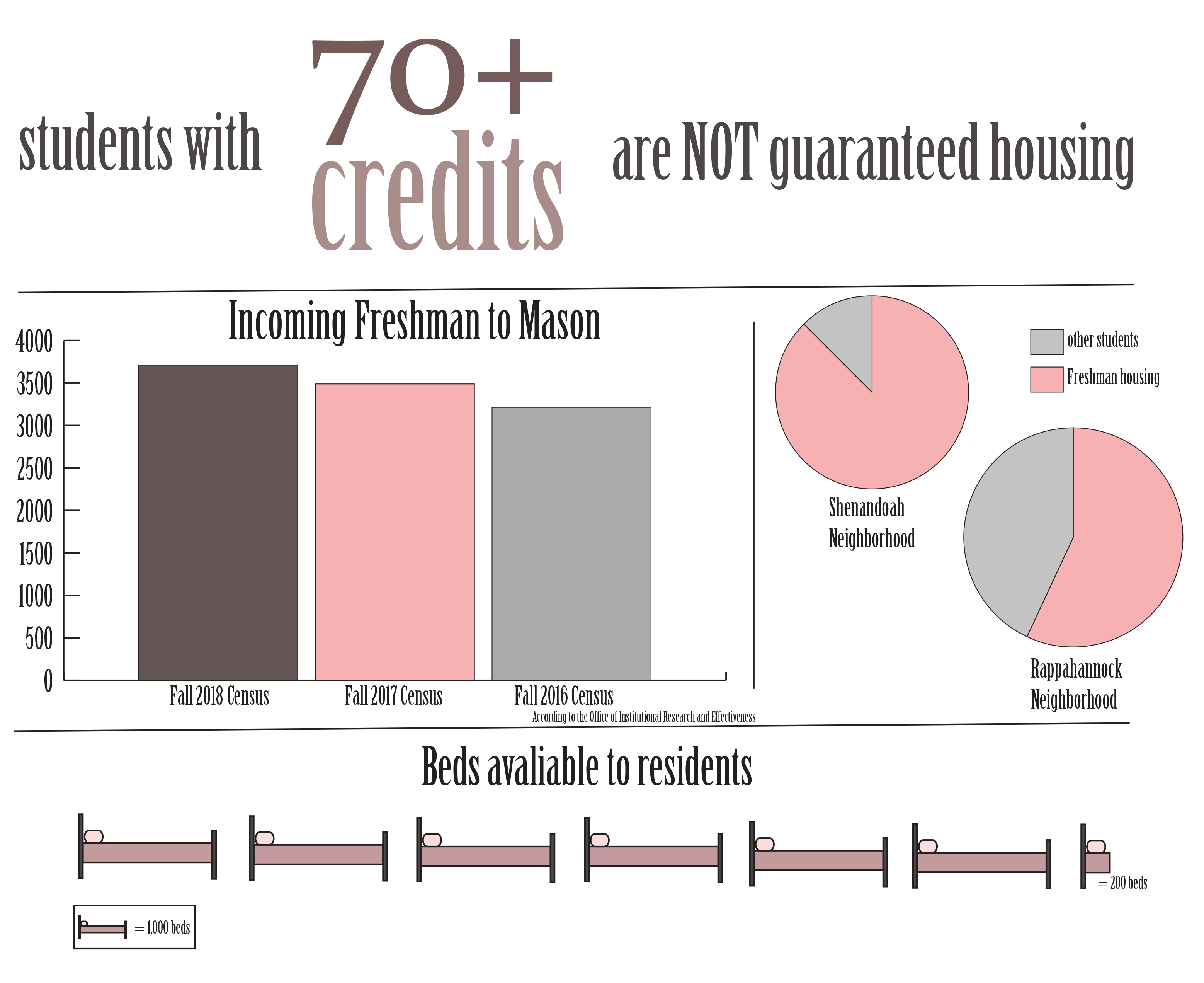

The Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness found in its Fall 2018 Census that the amount of new freshmen seeking a degree from Mason was 3,711 students. This number has increased by more than 300 since the Fall 2017 Census and 500 since the Fall 2016 Census.

A majority of the Shenandoah neighborhood is dedicated to freshman housing, including Presidents Park, as well as a significant part of the Rappahannock neighborhood. In total, nearly 90 percent of Shenandoah and over half of Rappahannock dorms are freshman-only.

Chris Holland, the assistant dean of university life and the chief housing officer, said, “We have 6,200 beds that are available to our residents. A good majority of those go to freshmen, living-learning communities and other unique demographic areas that are already kind of pegged out as ‘You are part of one.’ Those are the ones that make up the guaranteed beds.”

The space that is left for on-campus upperclassmen students includes the entire Aquia neighborhood of Rogers, Whitetop and the Mason Global Center, as well as dorms such as Eastern Shore, Northern Neck, Liberty Square, Potomac Heights, Hampton Roads, Piedmont/Tidewater/Blue Ridge/Sandbridge and the student townhouses that are located on Chain Bridge Road. It can be difficult to tell how many upperclassmen students are living within these spaces, as many sophomores live in these dorms as well, leaving fewer juniors and seniors able to live in the dorms and apartments that Mason provides.

“Last year, what happened is the number of students that actually applied was greater than our forecasting numbers,” Thierry said. “And then also we were like, ‘Okay, so we have more students applying than we have beds, but what is our melt? What do we traditionally see as people that probably won’t pick a room?’”

Thierry describes the ‘melt’ as the difference between the amount of students that apply for on-campus housing or state they wish to apply for on-campus housing and the amount of students that go on to select a room and complete the on-campus housing process. Housing anticipates it, and has data from the past several years to prove this theory.

This occurs because Mason’s housing application comes out early in the spring semester each year, and often circumstances that can prevent students from living on-campus such as graduating or transfering are not going to become final until the next year becomes closer.

Even with the melt considered, Housing did not know if they were going to have room for everyone who wanted to live on-campus the following year. “And so the decision was made with a lot of people that we’re going to tell a group of students with the highest number of hours at Mason, completed at Mason, … that we might not have enough beds at the end of the day to offer you a space at this time,” Thierry said. They were told that they would be placed on a waitlist and could not go through the traditional housing application.

On why Mason went with credit hours instead of another way, Thierry said, “That is a very traditional way to do it as far as when you have to prioritize students living on-campus … The students that want to live on-campus traditionally are … our freshman and sophomore students want that campus experience and we found that … when you are looking at the whole lifecycle of a student first-year to their fourth or fifth year depending on their program, those first two years are kind of your sweet spot, you know?”

She continued by stating that universities want to set students up for success but also ensure that students who want to have that on-campus experience are able to have that experience.

Nowhere on Housing’s website did it say that space was guaranteed for upperclassmen. “We have been very lucky at Mason that in the past any student who wanted to have housing, we were able to provide housing for them as upper-class students because we always had a group of upper-class students who didn’t want housing,” she said.

Other colleges and universities in Virginia grant upperclassmen students the right to live on-campus through graduation even if space is not guaranteed, whether the student is a senior or not.

At the University of Virginia upperclassmen are not guaranteed on-grounds (the university’s term for on-campus) housing. If students choose to live in the same building and room the following year, they are given priority to live there as long as they apply at the correct time. No difference is made between seniors and other upperclassmen in the process.

At James Madison University (JMU) and Virginia Tech, there is no difference between how seniors and other upperclassmen access housing selections as well. Tech does not guarantee their housing, but upperclassmen students are entered into a lottery if they choose, allowing most students to remain on-campus. At JMU, upperclassmen get space based on when they sign their housing contract, not the amount of credits they already have. When upperclassmen sign their contract, their housing process becomes guaranteed.

“We felt that we would have beds become available later, we really did,” Thierry said about the email they sent to upperclassmen notifying them of the decision that Housing had made. “We just didn’t want to set up a situation where students were told they’d have a bed and then they wouldn’t have a bed.”

Powell wished that they had sent out an announcement before the email came or before they started the application process stating that upperclassmen might not be given housing the following year. “It was just a shock, because it came in spring and right when people are [going] into next year and expecting to have housing,” she said.

Holland mentioned using social media including Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram as well as email, website and potentially campus-wide town halls to communicate future housing changes.