BY SAVANNAH MARTINCIC, STAFF WRITER

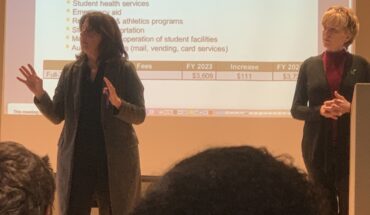

Two weeks ago I attended Andrew Yang’s campaign rally here on campus. While I was swept up in the excitement that the crowd of almost 2,000 created in the Center for the Arts, I could not help but be bothered by something.

Throughout the rally, everyone from Yang’s volunteer staff to Yang himself celebrated a huge fundraising achievement: raising $10 million in the past quarter. Monumental, exciting.

Why is how much money a candidate raises for their campaign always such a big deal? Well, when Yang announced his fundraising achievements, he was really telling the crowd that he is a stakeholder in the election. How does one become a stakeholder? Money.

Over the past 100 years, campaign spending has skyrocketed, especially between 2000 and 2012 when the amount of money spent by candidates more than quadrupled. In the 2016 presidential election alone, President Trump and Hillary Clinton spent a combined total of $1.16 billion.

Campaign money comes in the form of small and large donations from passionate citizens, special interest groups, political action committees (PACs) and candidates themselves. Super PACs, which are independent from campaigns, are also surging. These groups allow candidates and big donors to get around the limits the government has attempted to set on campaign spending.

Not only are donations necessary to support the staff, airfare, speaking engagements and advertisements that are crucial for a campaign, they also prove a candidate’s ability and credibility.

To even qualify for the Democratic debate this November, candidates must meet a donor requirement. By the time of the debate, a candidate must have received donations from at least 165,000 unique donors over the course of their campaign. This number will only continue to rise as we get closer to 2020, effectively narrowing the candidate pool.

The question is: Why is it so expensive to run for president in America?

The candidate you remember the most is the face you see the most. The candidate’s name you remember the most is the one you hear the most. Through campaign ads, candidates are buying our votes, meaning the candidate who can spend the most can typically earn the most votes.

Couple the high prices of a campaign with the absurd length of presidential elections and you get more of a spectacle than a political competition.

And while campaign spending has exploded within the past few decades, this is not a new concept. Early on in our political system, men of means, money and education assumed governmental positions.

With the start of the Industrial Revolution and the improvement of communication and transportation, politicians had to move from personal persuasion to mass persuasion at rallies and conventions. The unintended consequence of this expansion of democracy is that politics became a big business. And so began the journey to growing campaign costs.

This long-standing intersection between money and politics has no shortage of scandals attached to it. The son of Governor Huey Long, who wracked Louisiana with corruption, once even said, “The distinction between a large campaign contribution and a bribe is almost a hairline’s difference.”

It all just seems a little hypocritical, especially after hearing countless candidates from both parties talk about what financial improvements they plan to make for the working class.

So, sure, we could call it an investment in our future, but have candidates ever really followed through with all their campaign promises? If we are endorsing candidates based on what they say they will do, should we not get a return on investment that is equal to what we put in?

In an ideal world, yes, but we have created a presidential system in which it is not important who has America’s best values in mind but who has the deepest pockets.