A Discussion About HIV/AIDS Awareness

A Discussion About HIV/AIDS Awareness

BY SABIHA BASIT, STAFF WRITER

The end of November at Mason marked Mason’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Week.

Many activities and events were conducted in collaboration with various organizations at Mason, including the Student Support and Advocacy Center (SSAC), Patriot Activities Council and fraternities such as Phi Iota Alpha Fraternity.

Events included an HIV workshop, a condom demonstration and a Project Condom fashion show. One panel discussion, “Living with HIV,” illustrated the reality of this disease.

The panel took place on Thursday, Nov. 29, in the Johnson Center (JC) Cinema. It was organized by Dr. Malda Kocache, a biology professor who teaches classes on HIV/AIDS synthesis at Mason.

The panelists, Mark and Neil, shared the trials and triumphs of life with the disease and gave advice to students on the importance of positivity and good mental health. They gathered to both end the stigma surrounding the sexually transmitted disease and discuss the importance of education and mental health.

Neil graduated from Mason in 2015. He grew up in southeast Virginia, in a conservative small town called Windsor. His high-school graduating class was comprised of 48 people. As far as he was aware, Neil was the only one who was homosexual.

“I had barely, if at all, any sex education,” Neil said. “I didn’t know what HIV was until I came to Mason. For me, HIV was never on the radar. I was very sheltered. I felt like it wasn’t a problem for me, and it was a problem [for people] who engaged [in] risky behavior. It wasn’t something that was going to get me.”

Neil said that southeast Virginia is a place where there is little discussion about homosexuality. “When I came to Mason, there was this community of gay men who wanted to have sex with me,” he said. “I’ll never forget the gentlemen I was speaking with on [the] Grindr app, who stated he was HIV-positive, but [it] was undetectable. I blocked him immediately [after], and that is one of my only regrets in life, because this is a person, little beknown to me, who I would become.”

Neil has been HIV-positive for five years as of Nov 22.

“I remember I went to my doctor’s office, and she said to me, ‘Neil, you have HIV,’” he recalled. “It felt like I got hit by lightning. I felt the shock from the top of my head all the way to my feet. Ironically enough, it was not the … worst news I’ve gotten.”

He continued, “I truly believe that was one of my first deaths of my life, … the death of myself prior to the diagnosis, and then shortly afterwards, the resurrection of myself after the diagnosis. Because I changed. I [came] to terms [with] the fact that if my smoking doesn’t kill me, HIV will. But … I have chosen to use what was given to me as [a way] to help other people, and to educate and advocate for [people with HIV/AIDS].”

A misconception the panelists addressed was that people see HIV-infected individuals and assume they are not suffering if they look healthy and vital.

“Everybody is fighting a battle you don’t know anything about. I [ask] you all to be kind to one another, because everybody is going to die. When you are dead, people are going to remember how you treated others, how you acted and what you said. People will forget what you gave them for Christmas three years ago, ‘but [people] will never forget how you made them feel,’” he quoted.

Mark had a different experience contracting the virus.

“I like to call my story a catastrophic love story,” he said. “After leaving South Carolina, I got a scholarship to attend NYU. I got a job [where] I made more money than my parents ever received. I [also] found love in New Jersey. … [The relationship] lasted three and a half years.”

Despite living together, he had conflicting feelings about his partner. Mark eventually found out that his partner was HIV-positive and had given it to him.

“Once I found out, it was catastrophic to me because I was the person who followed all the rules,” he recalled. “I went to school. I graduated. I got a job. I [did] have random sex, but I always used protection.”

Mark continued, “In my head, the stigma of HIV was, you get [HIV] because you sleep around and I thought that would never be me. In South Carolina, [HIV] is not something you talk about. Being gay isn’t something that is celebrated, and essentially I just had a lack of knowledge.”

When he first experienced the symptoms, Mark went to multiple doctors. Instead of testing him for HIV, they all treated him for relatively minor illnesses such as strep throat.

He explained, “I went to the doctor and said, ‘You need to test me for HIV,’ and their response was, ‘No, we don’t.’ Because statistically, if you look at my profile, you wouldn’t think I would be HIV-positive. I was in a long term relationship, I made a certain amount of money [and] I had two degrees, so my profile … led the doctors to think I was not HIV-positive. They finally did the test, and it was positive.”

After testing HIV-positive, infected individuals face the psychological effects of their diagnosis.

“There was a night in which I considered taking my life,” Mark said. “There was no point for me to live anymore. The only thing that kept me alive [that night] was the fact that I was going to try my music. My music gave me the reason to live.”

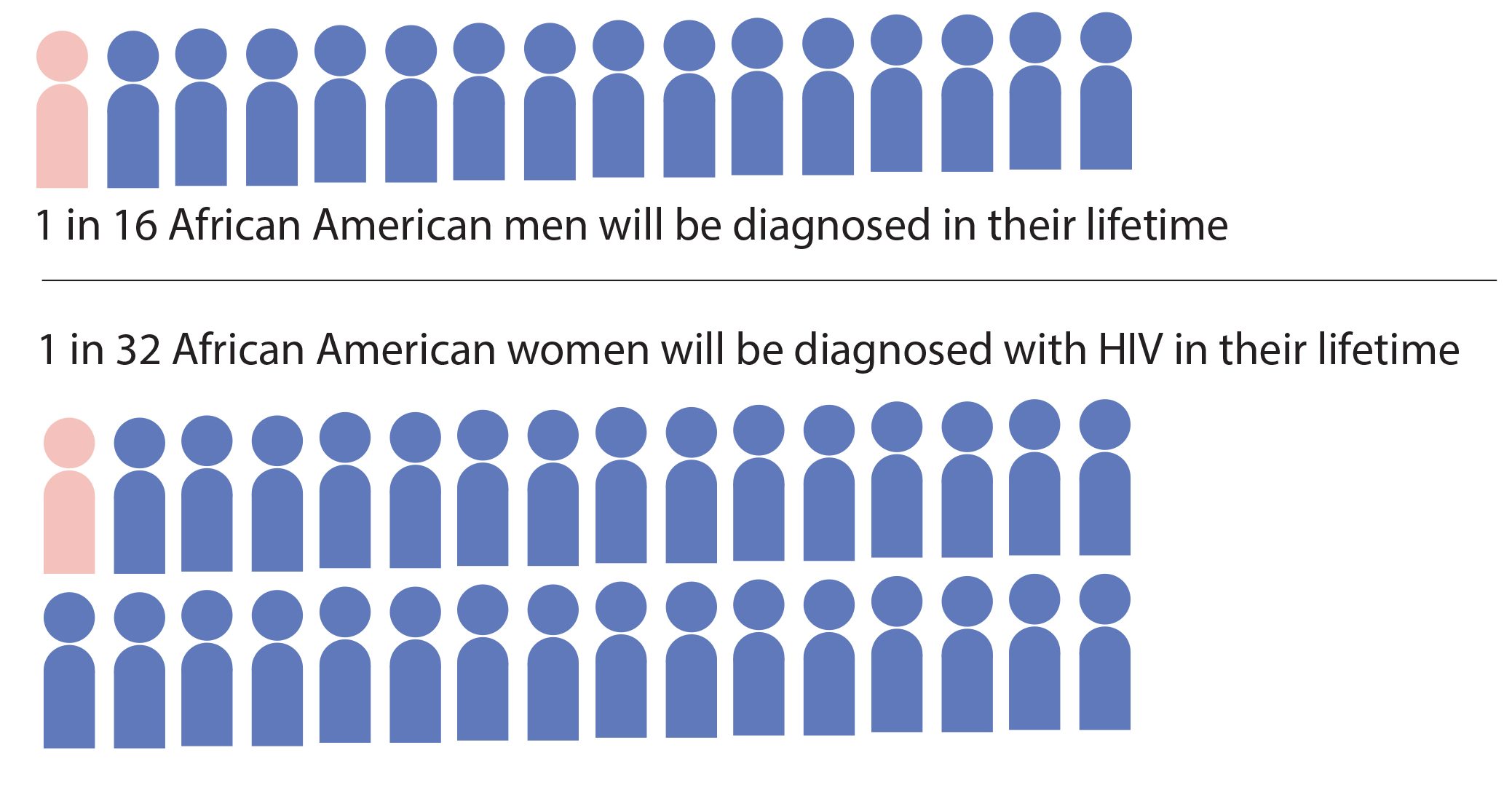

Another aspect of HIV that people should be aware of is that it is a disease that largely affects ethnic minority groups.

According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse, “Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of new HIV infections among MSM [men who have sex with men] occurred in minority men (Black/African-American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian/Pacific Islanders and Native American/ Hawaiian).”

One of the reasons why Mark decided to open up about being HIV-positive as a black male was to raise awareness and help break the stigma.

“Men of color, specifically LGBTQ[+] men or women of color, have the highest risk of contracting HIV, and the very confusing thing about that is that we are the population that knows the very least about it, whether it’s because [they] don’t access it or is not provided,” Mark said.

Both Neil and Mark agreed on the fact that education, awareness and destigmatization of homosexuality are key to establishing a society that does not discriminate against HIV-infected individuals.

“There should definitely be more education about HIV to younger people,” Neil said. “I think it’s a disservice to not know about HIV. The United States [has a] very regressive teaching agenda. [The states are] very Eurocentric, heterocentric. It makes me mad, because that is not teaching anything of value.”

Both Mark and Neil have an undetectable viral load, meaning that although they are not cured, there is only a small number of copies of the virus that are present in their blood (under 200 copies of virus per mL of blood). They both agreed that people should largely understand the difference between being detectable versus undetectable for HIV.

According to the Center of Disease Control (CDC), “HIV … weakens a person’s immune system by destroying important cells that fight disease and infection. No effective cure exists for HIV. But with proper medical care, HIV can be controlled.”

In 2017, 37 million people were living with HIV around the world.

Information for graphics gathered from the CDC, HIV.gov, and NHCOA