CAPS underfunding amid growing mental health concerns impacts treatment

BY HAILEY BULLIS, ASSISTANT CULTURE EDITOR

Mental health is a tricky and hard-to-navigate subject, and with national health trends on the rise, Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) is trying to help all students.

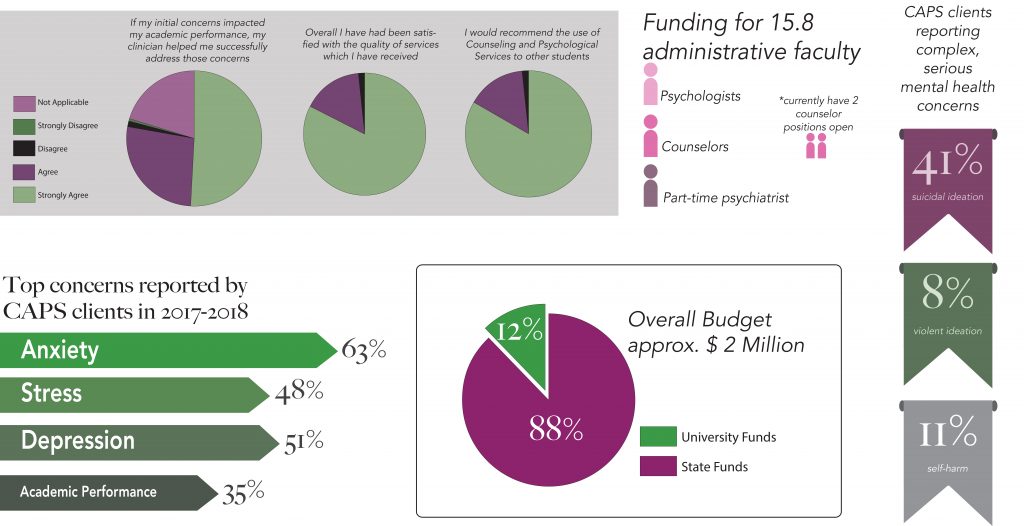

The use of mental health offices at universities has increased by 50 percent in the last ten years according to Dr. Rachel Wernicke, executive director of CAPS. This includes CAPS, which receives approximately $2 million per year. Ninety-six percent of this budget goes to paying 23.6 full-time personnel/trainees and 20 part-time workers.

Last year, CAPS served 1,682 Mason students for direct clinical services according to Wernicke. Mason’s office mirrors the national trend that more students are using psychological services. Of those students, 41 percent reported recent suicidal ideation, 11.8 percent reported recent self-harm and 8 percent reported violent ideation.

To meet the accreditation standards of the International Association of Counseling Services (IACS), CAPS is required to have one counselor for every 1,000 to 1,500 students. However, with current funding, CAPS only has enough staff for one counselor per every 2,341 students– well below the accreditation number.

“I wish we could do better … I can tell you that we’ve got the funding for 15.8 full-time clinicians,” said Wernicke. “By our accreditation standards, we should actually have 24. So I’m advocating for additional staff, at least 24, because the IACS ratio is one counselor to every 1,000 to 1,500 students. But resources, I think everybody at Mason needs more resources. Of course I would like to be able to serve more students.”

The CAPS office serves Mason students in many capacities. With individual therapy, group therapy, workshops, faculty/staff consultation, academic coaching, psychiatric services and more, the office tries to meet the needs of every student on campus.

Along with in-person resources, CAPS recently started their Therapist Assisted Online (TAO) program, an online system that allows students to access self-help modules, giving students a different support system option. CAPS also partnered with the JED campus initiative this year which aims at enhancing emotional health, substance abuse prevention and suicide prevention efforts on college campuses.

Last year, CAPS did an Internal Client Satisfaction Survey which showed that 83.2 percent of CAPS clients strongly agreed they were “satisfied with the quality of services” they received from CAPS, with another 16.1 percent agreeing.

Another survey done last year by the Student Health Advisory board (SHAB) found that while the students’ overall impression was positive, “students feel that CAPS treats everything either as an emergency or as something that can wait.” The survey concluded that “it appears that the perception of the triage process is that if a student is not suicidal or attempting to harm themselves or others, that their case is dismissed and can take weeks to be seen by a therapist.”

Two students who wished to remain anonymous shared this concern.

The first student, Kate*, first visited CAPS to deal with her trauma after she was sexually assaulted in her dorm her freshman year. She was diagnosed with PTSD and prescribed Xanax and Paxil to treat her mental illnesses by a counselor back home.

“In the initial phone call and even in my first meeting with a counselor from CAPS, they only really were asking if I was suicidal or if I was going to hurt someone else or myself,” said Kate. “So I felt like that was kind of the only concerns they had … when dealing with my mental health. They didn’t really give me resources for dealing with day-to-day life. I just felt like the only thing they cared about was if I was going to kill myself because that would make the university look bad and they would be liable for that kind of stuff.”

Kate described how she was unable to see the on-campus psychiatrist from January to March. During that time period, she began to abuse her prescribed medications, and she began to smoke marijuana, something she was very open about with her counselor.

Wernicke said that during that time, their on-campus psychiatrist was on leave. Although Wernicke was not at Mason during that time, she assumes that students seeking psychiatric help were referred off-campus or to Student Health when the psychiatrist was not available.

“I felt so alone, and there was no one really to help me with what I was going through. I started to cope with my problems, like if I was having a meltdown or there was some kind of conflict going on in my life and I would be like, ‘welp this sucks, gonna pop some more Xanax then I’m prescribed,’ so that was really frightening, just being that addicted to something,” Kate said.

Kate used marijuana as a way to cope with her mental illnesses and felt that the counselors at Mason focused heavily on getting her to stop.

“Something else I would do to cope with my mental illness was just smoking a lot of weed every day pretty much, which, I was very open about my drug use with counselors at Mason,” she said. “… Kind of, like, the main concern of theirs was that I should just stop smoking weed, and I was like, ‘yeah, I could stop smoking weed but it’s the only thing that kind of balances out the crazy side effects that I would get from the antidepressants as well.’”

Kate also went to group therapy, which is offered to Mason students who are clients of CAPS. There are eight different groups aimed at helping different types of students. Kate attended the Surviving to Thriving group, which is geared towards students who survived sexual assault at some point in their lives. However, while the retention/success rate of the groups tends to be high, Kate did not have a positive experience with her group. She was looking forward to the group, as she hoped it would give a chance to receive “peer to peer” counseling.

“I was really excited about that program and I was excited to be in a group setting where I could talk about my feelings, because in the one-on-one counseling, I felt like I would just cry a lot and it was kind of hard to like make any progress,” Kate said. “… It just kind of felt weird one-on-one, especially talking to an adult about that kind of stuff was kind of annoying. So I went to group and there were only two in the group, me and one other girl, and two counselors. So there was Sierra Scott and Irene Valentine. So there [were] only two counselors and two students in a group counseling setting.”

Typically, group therapy has six to eight group members, but the sexual assault group has a hard time finding participants, Wernicke said.

“We’re not alone as a campus in having some difficulty recruiting folks into group therapy because many students … prefer the one-on-one modality, and it can be scary particularly with sexual assault to share your experience in a group,” Wernicke stated. “So sometimes that group can be a little bit harder to fill, although we certainly try, and we’re offering that group again.”

Another student, Drew*, said he felt brushed off by CAPS after he attempted to receive treatment for his anxiety and depression. Drew was referred to off-campus treatment after speaking with a counselor.

At the time, Drew did not have a car to get off-campus to receive treatment. Referring to when he asked if there was anyway that CAPS could see him on-campus, he said, “It was very weird because I asked, ‘can I see someone on-campus, and they were like, ‘well, kind of but not really,’” he said. “It seemed very wishy washy.”

Drew felt the process was very mechanical and expected to set up a regular meeting with CAPS. After his initial encounter, Drew has been hesitant to reach back out to CAPS.

“I really don’t want to have to like deal with going through a phone call, waiting a week to have a phone call to set up another meeting to then get told to go somewhere else again,” he said. “It would be nice if the university could give them way more resources, because … the school administration always talks a big game, like, ‘you should take care of yourselves’ and having students take care of themselves is not bringing in a few cute dogs on-campus once a year…like when it’s stressful, that doesn’t actually fix anything.”

In response to these issues, Wernicke said, “That’s actually kind of the bind that we’re in, is that we have few resources, we have students who are coming in with great need and many students who are coming in with very few resources and that’s kind of a perfect storm… so we end up serving those students longer and we do try to find providers in the community who can get here, who are close by, and we have a referral database on our website.”

The top four concerns for CAPS are dealing with mental health, including anxiety, depression, stress, and academic performance, according to Wernicke.

According to the 2016 Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors Annual Survey, which Mason participated in, schools that enroll 35,001 or more students see a drastic increase in hospitalization, attempted suicide and suicide than schools with less students. Mason currently enrolls over 37,000 students.

The office focuses more heavily on short-term care rather than long-term, according to Wernicke, a trend that is not limited to just Mason. According to a 2016 annual report done by Center for Collegiate Mental Health, “Over six years, counseling center resources devoted to ‘rapid access’ services increased by 28 percent on average, whereas resources devoted to ‘routine treatment’ decreased slightly by 7.6 percent.”

“I would love to be able to see students long-term, and I think that really what at Mason what needs to happen is we also have to be able to absorb more students and be able to serve more students, which I think will still mean that we’ll be in a short-term model,” said Wernicke.

Junior conflict analysis and resolution major Sarah Ahn felt that while her counselor went above and beyond to try and help her, she does not know if she would have received the same treatment if she had received a different counselor.

“It could’ve been better. First of all, they don’t do long-term counseling… they just do short-term counseling, and it just doesn’t feel like there’s any help,” she said. “The counselor that helped me, the only reason they actually helped was because he was going way out of his way to help me. He was like ‘yeah, we don’t do long-term counseling, I can do what I can,’” said Ahn.

Despite this, CAPS does not have a hard limit on how many sessions a student can receive, and the session limit is instead decided case by case, said Wernicke.

In the future, Sarah Ahn wants CAPS to be able to support more students.

“They just need to allocate more resources to CAPS, like maybe get more counselors, like more support… you should have the ability to help these students,” Ahn said.