In light of the recent events in Ferguson, Missouri, Mason faculty and organizations are starting conversations on campus about race and inequality.

On Sept. 4, Mason’s African and African American Studies and Women and Gender Studies departments along with the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Multicultural Education and Film and Media Studies hosted “Policing the Black Body,” a public forum that explored the deaths of young black men such as Michael Brown.

Brown, an unarmed eighteen-year-old black male, was shot by white police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri on Aug. 9. In a report from KSDK-TV, St. Louis, St. Louis County Police Chief Joe Belmar said the fatal shot was fired due to Brown physically assaulting the officer and reaching for the officer’s gun during a struggle. Though there are reported eyewitness accounts that dispute this claim from the police.

“We felt like students needed an opportunity to have a public forum to discuss how they were feeling” said Mika’il Petin, the associate director of African and African American Studies. “Our sense was that students were frustrated, especially students of color, but students in general.”

“Policing the Black Body” is part of a series themed around “Policing the Body” created in the spring by African and African American Studies and Women and Gender Studies. The events in Ferguson highlighted the relevancy and applicability of dialogue about inequalities surrounding black bodies.

“I never could have imagined that this theme that we selected would become so real,” said Dr. Wendi Manuel-Scott, the director of African and African American Studies and a panelist at the event.

In addition to Manuel-Scott, the panelists included student representatives from the Black Student Alliance, a trained psychotherapist and clinical psychologist and a police officer and police planner at the Prince William County Police Department.

Chris Jenkins, an assistant local editor of the Washington Post and producer of Brother Speak, was a guest speaker at the event. The video series Brother Speak explores the lives of black men. During the “Policing the Black Body” event, Jenkins shared video from Brother Speak shot in Ferguson with the audience.

“What we tried to do in Brother Speak was be a little bit more thoughtful and quiet in our conversation about what men were feeling and what men observed and what men were doing, in particular African American men were doing, in Ferguson eight days after Michael Brown was killed,” Jenkins said.

Jenkins noted that there was a lot of anger and riots seen in the media days after the event in Ferguson.

“Those things did happen and they should be recorded, but they weren’t the only things going on,” Jenkins said. “What I think Brother Speak Ferguson tried to illustrate was that there were a lot of internal conversations going on regarding how hurt [men] felt as fathers, how concerned they were about how the events in Ferguson were consistent with some things they experienced with police officers in that community and that many of the things they saw were consistent with how African American men in times over the years were treated in places like Ferguson.”

Jenkins hopes Brother Speak will reveal the multi-dimensional character of the events in Ferguson.

“What I hoped they got out of it was there are many, many dimensions to men’s responses to the event on Aug. 9,” Jenkins said. “I hope they got a clearer understanding of the deep-seated emotions that Ferguson elicited, but also that there are different ways of telling stories of incidents like Ferguson.”

In a story from USA Today’s Paulina Fizori, violent crime has decreased in Ferguon according to FBI data, but out of all the arrests made there, black people account for the most.

“Last year, black residents accounted for 86% of the vehicle stops made by Ferguson police and nearly 93% of the arrests made from those stops, according to the state attorney general,” Fizori wrote. “FBI statistics show that 85% of the people arrested by Ferguson police are black, and that 92% of people arrested specifically for disorderly conduct are black.”

There is also a large shift in the demographic between Ferguson police and community. Beginning as a predominantly white town in 1970 with 99% of the population being white, that number has dropped to 29%, with 67% of the population being black. The Ferguson police department, however, does not reflect this demographic. Out of 53 officers in the department, only three of them are black.

This raises questions when data from policing agencies are provided by the state’s attorney general’s office and compared across a racial breakdown. St. Louis Post-Dispatch writer Walker Moskop wrote,”Last year, blacks, who make up a little less than two-thirds of the driving-age population in North County city, accounted for 86 percent of all stops. When stopped, they were almost twice as likely to be searched as whites and twice as likely to be arrested, though police were less likely to find contraband on them.”

Jenkins used his experience working with media to show students the power they could have in changing how black bodies are portrayed.

“I felt it was important to talk to students about the power that they could have in creating positive images regarding how African Americans are portrayed in social media and mainstream media,” Jenkins said. “Images of African Americans can be more richly portrayed by this current generation through social media and the tools that we have at our disposal which include cell phone videos, Twitter, Facebook and those sorts of things.”

Before the emergence of technology and social media, Jenkins said it was more difficult for students to make change happen.

“For a long time, generations of young people were not able to have a real impact on the narrative of how they were portrayed in the media…today young people and the millennial generation have an opportunity to create it’s own narrative,” Jenkins said. “That’s really an unprecedented phenomenon that sometimes I think is taken for granted by young folks, and I really wanted to impress upon the students there that this is a time where they can create their own narratives about what is important to them and how they are portrayed in the media.”

Petin also clarified that although “Policing the Black Body” was focused on black bodies, it was meant to be inclusive.

“Just because the event was talking about black bodies in a very abstract sense, but also a very concrete sense, my hope was that the students of African descent, the students of European descent, students from diverse backgrounds, that they felt welcome,” Petin said. “It was an opportunity for them to connect with people that they haven’t met before, that they hadn’t seen in a while, but more than anything to come, to learn, to discuss, to leave enriched, to leave invigorated. So I’m hoping that even if students weren’t transformed, something in that event resonated with them.”

The Diversity Research and Action Consortium recently partnered with the College of Education and Human Development on a Discussion Panel on “Ferguson and the Policing of Minority Communities” on Sept. 15 to discuss racial overtones and bias in the media and criminal justice system. The panel included Colonel Edwin Roessler, Chief of Police of Fairfax County Police Department. The discussion focused largely on how people are policed in our community and how people can get involved and learn more about policies.

One of the panelists, Associate Dean for University Life Dr. Joya Crear discussed how Ferguson relates to injustices that might be seen in Mason’s community. According to Crear, students can report biased policing on campus with a “Bias Incident Recording.”

According to the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Multicultural Education website, Mason defines a “bias incident” as, “an act of discrimination, harassment, intimidation, violence or criminal offense committed against any person, group or property that appears to be intentional and motivated by prejudice or bias. Such are usually associated with negative feelings and beliefs with respect to others race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, age social class, political affiliation, disability, veteran status, club affiliation or organizational membership.”

Any incidents that fall under this category can be reported with the Bias Incident Report Form on the ODIME webpage. The webpage does, however, point out that bias-motivated acts may be protected as free speech.

Like Crear, Dr. Wendi Manuel-Scott, the director of African and African American Studies, encouraged students to find and use their voice to create change.

“I think students from all backgrounds need to engage in these kinds of difficult and uncomfortable conversations around race, and admittedly they are not easy conversations to have,” Manuel-Scott said. “If we want to be better in terms of our diversity, it means having difficult conversations around race.”

Manuel Scott believes the events of Ferguson not only provided a good discourse, but inspired students to take action.

“Ferguson just blew everything up in terms of exposing the real, raw realities of racism in America and what Americans and Mason students witness on the streets of Ferguson made it impossible to turn away, made the rawness of racism in America undeniable for so many people,” Manuel-Scott said. “And I think for Mason students in particular, they’ve probably never seen anything like that…everything they’ve been taught in school has suggested that that is the past, that that’s done… And then Mike Brown was killed and then Ferguson streets were aflame. I know I was moved, but it was very clear to me that young people were also very moved as well.”

One student was moved enough to contact Manuel-Scott to organize a march on campus.

“I was very excited that this was going to be a student-driven event,” Manuel-Scott said. “So often, as director, I plan events and want students to come, but in the case of the Mike Brown march, this was that something students felt compelled to do.”

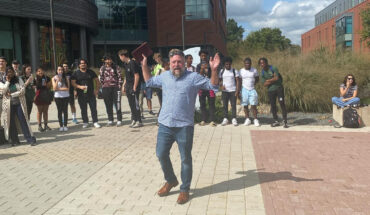

The march took place during the afternoon of Aug. 25, the first day of classes.

“It was beautiful. There were students covered in hijabs, white students, black students, Latino students and it was just a beautiful representation I think of what happens when people are willing to be in communication, be in dialogue, and willing to take action,” Manuel-Scott said.

Manuel-Scott revamped her AFAM 200 course syllabus around the policing of black bodies and the criminalization of black bodies.

“It’s such an important moment, that to not fully engage it as a scholar, to not fully engage it as a professor I think does a disservice to our students,” Manuel-Scott said.

Manuel-Scott also noted that events like “Policing the Black Body” and upcoming events apart of the “Policing the Body” series are good starting points for conversations about inequality and the pain or trauma that comes with it, but that for change to happen it is necessary for students to continue to find their voice to create change.

“I think it’s important to create spaces where people can be honest about what they’ve experienced, about what they feel and know to be true,” Manuel-Scott said. “But that cannot be and should not be the end.”

Photos by Erika Eisenacher and Amy Rose