BY STEVEN ZHOU, STAFF WRITER

Earlier this year, Stanford graduate students who had no other means of affording meals during winter break were reported to be foraging for food from trees on campus. As extreme as that example may be, the archetype of the “starving graduate student” probably plays out far more often than we would like to acknowledge.

While these trees might provide the occasional piece of fruit, we won’t find the solution to our real problems — stipends and tuition dollars — growing on their branches.

For the most part, university administrators face the pressure to solve this problem. “Increase funding for graduate students!” is the mantra for many.

This year, I have the privilege of serving as a representative for my department at the Graduate and Professional Student Association (GAPSA) general assembly. At our latest meeting discussing the topic of compensation and funding, the question raised by most of my peers was: “When will they increase stipends and compensation?”

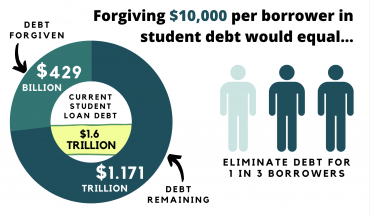

I fully support increasing stipends and tuition waivers. Living in the D.C. metro area is not cheap. The fair living wage for a single adult in Fairfax County is $17.44 per hour, and the current $16,000 minimum stipend at Mason works out to about $15.38 per hour.

But here’s the concern I have over a broad-brush increase of stipends: The money has to come from somewhere.

Too often, increasing stipends means less opportunities for graduate students. It’s been called the “whack-a-mole” problem: Increased costs from increased stipends will need to be offset by reducing costs from other benefits or reducing the number of positions eligible for stipends in the first place.

In fact, a 2018 study by the Midwestern Higher Education Compact found that increasing “standards of care” required to support students and the rise of tuition discounting are some of the primary drivers for today’s outrageously high tuition costs.

Yet another empirical study conducted by data researcher Tom Schenk in 2010 found that unionized graduate student wage gains were predictably offset by reductions in other student benefits such as healthcare and tuition waivers.

This is basic mathematics: given a limited pot of money, if you have to increase the amount allotted to each person, you’ll be able to give money to fewer people. And contrary to popular belief, graduate students as TAs can cost a lot of money to the university.

A University of Chicago law professor pointed out that the typical Ph.D. student costs the university upwards of $500,000 in terms of lost revenue, stipends, healthcare, etc.; such costs often dwarf the cost of hiring an adjunct to teach the course.

We see examples of this already in faculty hiring. When faculty at Wright State University went on strike last year, about 20 percent of courses were canceled, and the university simply turned to hiring adjuncts instead.

If you make graduate students too expensive, then administrators will have no choice but to accept or fund fewer graduate students.

It’s actually a subtle yet insidious form of oppression. The result will likely be that those who are already fully funded will see increases in their paycheck, while those who hold part-time assistantships will find their positions cut due to the rise in minimum stipend. It’s taking from the poor to give to the rich.

Here’s my point: It is fair to ask for more money, but we also need to ask where it will come from.

We seem to have this assumption that it’s us starving graduate students against the power-hungry, stingy administration. But every person I’ve talked to in the administration at Mason has been fighting for the cause of students. Administration and graduate students are on the same team. We’re both trying to find ways to improve student funding. Even from a business point of view for the university, more funding means more students which means more revenue, higher rankings, more donors and more alumni.

Students and administration should be working together to make this happen.

The next time someone asks about increasing stipends, I’d like them to also explain where that money would come from. There are some good ideas out there. Mason’s continued push for online programs allow for tuition dollars to come in from around the world to help raise money. We have an amazing team dedicated to obtaining research grants that can provide funds for student research assistantships. Some other colleges have gotten creative, going so far as to rent out facilities as wedding venues to raise funds to help students.

I started out by saying that we won’t find scholarship money growing on trees.

Perhaps I should amend that to say that it’s possible — if we plant the right trees.