A sustainable fashion panel discussion is held in the MIX@Fenwick

BY NAYOMI SANTOS, STAFF WRITER

As opposed to fast fashion, slow fashion values every aspect of clothing manufacturing, from the seeds that grow the cotton to the hands that sew the piece together. More and more, there is growing discussion surrounding the harmful fast fashion industry, as well as the emergence of influencers who commit to making the industry more sustainable.

Many Mason faculty and students are among these influencers. This dedication sprouted the Upcycled Fashion Challenge at Mason that asked students to create a new piece of clothing from an old or thrifted item.

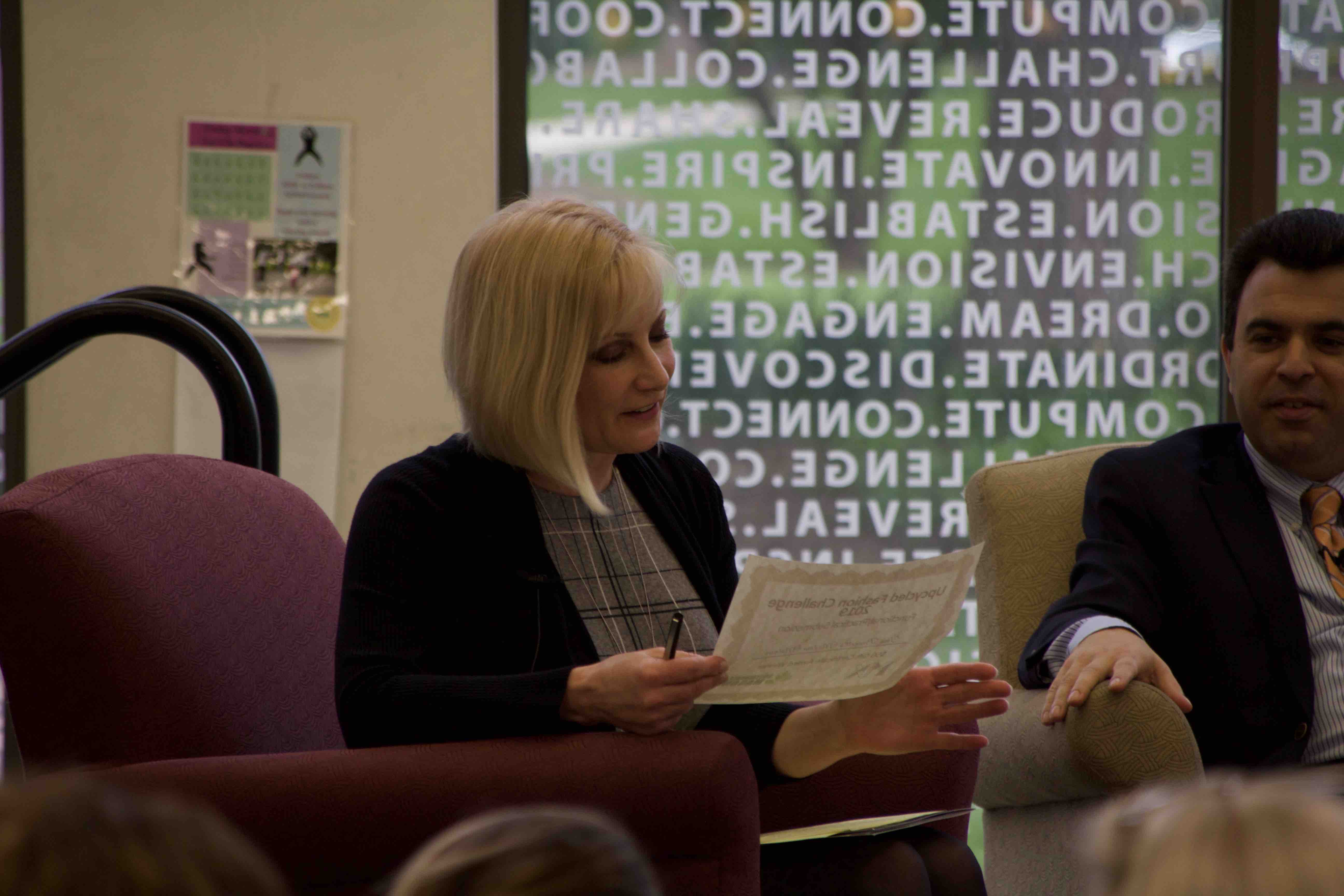

On Wednesday, April 23, the MIX@Fenwick hosted a sustainable fashion panel as the conclusion to the challenge.

The panel was moderated by Sharon Spradling, a professor of environmental and sustainability studies at Mason. The panelists were comprised of four people committed to bringing awareness as well as combating the many damages that fast fashion does to the environment and the lives of people.

One member, Avedis Seferian, is the CEO of WRAP, which is one of the world’s largest factory-based social compliance programs, dedicated to ensuring that factories around the world are safe and humane. Trisha Gupta is a printmaker and artist who advocates for the ethical manufacturing and usage of dyes in clothing. The last two members, Emma and Mary Kingsley, are the mother-daughter duo who founded Lady Farmer, a sustainable fashion label.

Slow fashion addresses all of the negative of fast fashion. “It turns the whole industry on its head,” Mary said.

While fast fashion focuses on the speed at which a product is made with the least expense attached, slow fashion pays attention to the actual process of making clothing. It considers every step.

So why is it important?

Fast fashion is a mega industry that millions of people partake in every day, while not aware of all the environmental and social concerns that are attached to it.

Slow fashion also addresses the cultural heritage aspect as well. Gupta spoke of the dyeing communities in India. “There’s a lot more interaction, there’s a lot more reflection,” Gupta said. Fast fashion eliminates all of that.

“[Fast fashion] is a symptom of the problem,” Seferian said. It is possible to make that amount of clothing without taking all of the damaging shortcuts, yet companies feel the shortcuts are a necessity, Seferian explained. “The supply must meet the demand,” he said. Therefore, consumer attitude is also an important aspect in the process as well.

During the discussion, the Savar building collapse in 2013 in Bangladesh was also brought up. “[The collapse] raised the profile of the importance of the issue,” Seferian said.

The building collapsed as a result of a structural failure, and killed 1,134 people—mostly female garment workers. It was later revealed that the building had shown signs of failure, yet workers were forced to continue working.

“There was a personal connection seeing all the brands attached to the factory,” Emma said.

The collapse placed the horrors of the fast fashion industry in the spotlight, and began the fashion revolution. The movement is dedicated to changing the industry so that both people and the environment are valued. In fact, Fashion Revolution Week this year was April 22-29, to coincide with the 6-year anniversary of the Savar collapse.

Each of the panelists hailed from different backgrounds, bringing different expertise to the fast fashion issue. “We look at the problem from different boundaries,” Gupta said.

Her expertise is in dyes and printmaking, as well as understanding the environmental concerns that each raise. Her work is in teaching people to dye more ethically and bringing traditional Indian dyeing practices to America. She teaches art and dyeing in various locations, such as schools and prisons. “I’m not limiting myself to certain populations,” Gupta said.

Similarly, Lady Farmer also seeks to bring awareness to the fast fashion industry by encouraging a sustainable lifestyle. “[We] want to source fabrics domestically and regeneratively,” Emma said. Their brand wants to be sustainable from the “ground up,” placing an emphasis on sustainable farming that does not hurt soil.

Still, Emma realizes the problems that could arise with sustainable products. “[It] becomes a privilege issue,” she said, due to the high cost of many of the products.

Seferian considered another aspect. “Sustainability itself must be sustainable,” he said. The economic tradeoff when it comes to sustainability is essential, including working with both the factories and companies when changing the game.

Those in attendance of the event also had the opportunity to ask questions to the panelists. The topic of second-hand fashion was brought up.

Mary talked about how second-hand fashion is a great alternative to the fast fashion industry, but there is an environmental concern with washing. The more that a piece of clothing is washed, the more microfibers are released. “Wear it, but wash as infrequently as possible,” Mary said.

In addition to the panel discussion, the event was also the culmination of the Upcycled Fashion Challenge, where all submissions were displayed and the winners were announced.

The event brought much of what makes fast fashion so hurtful to light, and taught many lessons that consumers can consider in the future.