How food waste contributes to climate change

“Mason’s food waste is approximately 30 percent of the total waste generated on campus…This means that the estimated amount of food waste was 303,000 pounds,” said Dustin Adams, the manager of Recycling and Waste Management for Facilities Management. (Megan Zendek/Fourth Estate)

An often overlooked contributor to climate change is food waste.

A Time article co-written by Raul Grijalva and Mason professor Michael Shank discusses food waste and how human beings can be large contributors to the issue.

The article stated: “Waste appears throughout the supply chain, from produce damaged at farms to retail packages that don’t properly store food, to our very own eating habits that lead us to discard food before it has passed its prime. And when this food goes uneaten, we waste the water and energy needed to produce it, harvest it and bring it to market.”

Grijalva and Shank go further to say that “if ‘food waste’ were a nation, it’d be one of the largest emitters globally, outranked only by China and the U.S.”

But the impact of food waste does not end at carbon emissions, there are also socio-economic consequences as well.

“Direct economic losses from wasted food total $750 billion annually, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the U.N. That hits the pocketbook of every single American, with an average cost per person in this country of $640 worth of wasted food each year,” the article said.

Another way in which food waste contributes to climate change is through industrial agriculture, said Danielle Wyman, the outreach and community engagement manager for the Office of Sustainability. Industrial agriculture practices contribute to about 30% of the world’s overall carbon emissions, Wyman said. She added that these emissions are created by everything from production, to irrigation, to processing and transportation.

So what does all this have to do with Mason?

Mason students also waste food, but unlike people who go to the grocery store with a certain amount of money to spend or a limited list of items to purchase, students have all-you-can-eat dining halls at their disposal. With meal plans like Anytime Dining, students can eat all they want, whenever they want.

“Mason’s food waste is approximately 30 percent of the total waste generated on campus. Total waste for FY15 was 1,010,000 pounds. This means that the estimated amount of food waste was 303,000 pounds,” said Dustin Adams, the manager of Recycling and Waste Management for Facilities Management.

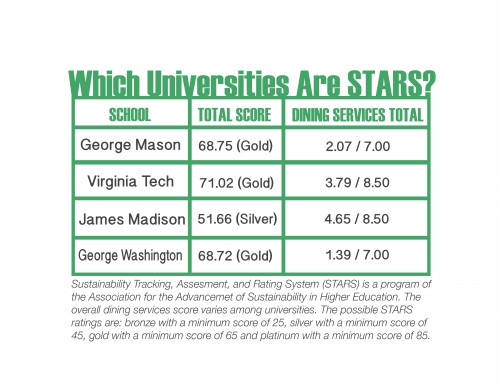

The amount of food Mason wastes is also reflected in the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS) rating Mason received from the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) in 2014. STARS is a transparent, self-reporting framework for colleges and universities to measure their sustainability performance, the AASHE website said. The four ratings a school can receive are bronze, silver, gold and platinum.

Mason was the first school in Virginia to receive a STARS rating in gold with a 68.78, the second best rating a school can receive. Only two other schools, UVA and Virginia Tech, have gold ratings out of the ten STARS participants in Virginia.

However, compared to these two other schools, Mason has a low point value in dining with a 2.08 out of a possible 7.00. Despite this low number, though, Wyman was quick to point out that Mason Dining has improved a lot over the last couple of years.

“Mason Dining is doing a lot. Since I’ve been working with them, about seven years ago, they’ve grown leaps and bounds in terms of sustainability,” Wyman said. She added that Dining has been working to improve their record keeping and recording in terms of sustainability practices.

In addition to better record keeping and recording, dining has started to search for ways to better deal with the food waste at Mason. This past September, Mason joined the Campus Kitchens Project, a national organization that has empowered student volunteers to turn wasted food into healthy, balanced meals for the community, and launched its own Campus Kitchen to address local hunger and food waste in the Fairfax community.

Caitlin Lundquist, the marketing director for Dining, said that so far this school year, Mason’s Campus Kitchen has recovered approximately 300 pounds of leftover food (as of Nov. 9) from the Globe and Southside dining halls and through university catering.

Zuri Gagnon, the vice president for the Campus Kitchen at Mason and an intern with Dining, said this leftover food creates several meals per week.

“This food turns into over 50 meals a week,” Gagnon said. “Campus Kitchens typically gets food that is already prepared but didn’t make it out to be served and prevents it from being thrown away.”

Another way that dining tries to reduce food waste is with the shape of their plates.

“The plates are smaller and all different shapes, triangles, long rectangles, etc. This encourages students to consider whether they need to get a second serving. We also do not have trays, which serves a similar purpose, inhibiting students from taking more food than they can eat,” Lundquist said.

Along with turning food waste into meals for the homeless, Mason is also looking to incorporate composting on campus in the future. Adams said composting accounts for 30 percent of Mason’s total waste and can be very beneficial to the Mason community.

“The most obvious [benefit is] the diversion [of food waste] from the incinerators and landfills. It can be converted into highly nutrient rich soil that is then sold to local citizens and farms to reduce the demand for manufactured fertilizers,” Adams said. “Composting is cheaper than regular trash, so it saves the university money, and may allow us to negotiate a discounted price on the purchasing of the finished compost product.”

Wyman explained that landfills harm the environment by producing greenhouse gases. Thus, composting is a more Earth-friendly option.

“[What generally happens with] food waste is it goes into landfills; in our case here in Fairfax County, it goes to the waste energy plant. [This food waste] generates methane, methane contributes to greenhouse gases, which contributes to climate change,” Wyman said.

Adams continued that Mason has worked to find a facility in the area that can compost on a large enough scale.

“We have recently identified a new composting facility in Prince William County that is working on building the infrastructure to handle the amount and type of material we generate,” he said. “The facility, Free State Farms, anticipates reaching full capabilities in July of 2017 and this will be the first viable option for Mason’s entire food waste diversion.”

In the meantime, Wyman says there are a number of ways that students can be more conscientious of the food they waste. She said getting students involved in Campus Kitchens, the food pantry and composting can all help reduce waste. The other way is through education.

“Get to know your food,” Wyman said. “Start asking questions. Where’s my food coming from? Am I ok with how it’s being produced? Then if you’re not, then how can you make some choices that you are ok with it.”

Wyman added that student action is the key to changing the way Mason handles its food waste.

“It’s just a little team of five of us [in the Office of Sustainability],” Wyman said. “We can shout this till we go blue in the face, but really, it’s when we get the students support and involvement [that] we see major change happening.”