BY ARJIT ROSHAN STAFF WRITER

A couple of weeks back I was having a (delicious) dinner at my girlfriend’s house, and while talking to her dad about my previous column on the minimum wage, the national debt came up. While sympathetic to the idea of “making work pay,” he felt that the wage subsidies would unfairly increase taxes on everyone else.

I retorted, “Well, minimum wage basically does the same thing. Regardless, the policy would probably be paid for by government borrowing anyways.”

“Well I don’t think we should be doing that either, the government has to stop spending more than it takes in or else we won’t be able to pay our debt,” he said.

“I heard we’re already in a lot of debt to China,” her mom chimed in.

In front of me was a textbook example of how the typical suburban American household perceives redistribution and government spending. Being an over-zealous guest (and a couple of glasses of wine in) I felt the need to explain why this wasn’t really true, and to offer a better way for people to assess economic policy. And I’ll do the same for you.

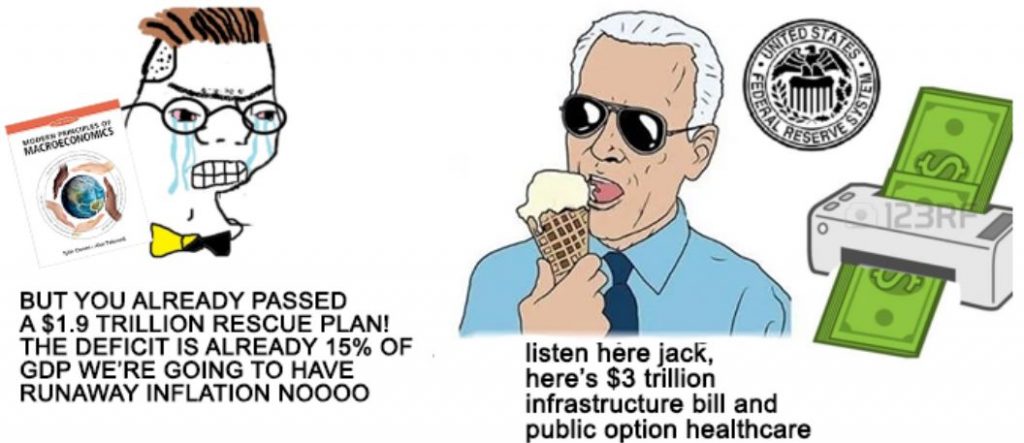

A $1.9 trillion relief bill, a $3 trillion infrastructure bill, 2 percent average inflation target, projected 3.7 percent real GDP growth, projected $2.3 trillion deficit, $28 trillion in national debt — what do these numbers even mean? A lot, but also, not very much.

For people to understand the macro-economy, there’s no need get into all these complicated numbers — it’s more revealing to dumb it down.

When people think of “the economy” they might vaguely picture a squiggly line with some tickers that they see on the news every day. But the economy isn’t a series of rates, charts and numbers with too many zeroes (how much is a trillion anyway?). It’s just a bunch of stuff. Red-blooded people working, factory gears turning, oil platforms drilling, and as the Ever Given reminded us, tons of goods on big boats. The economy is stuff and people, and with all the squiggly lines, it’s all too easy to forget that.

It’s important to recognize that economists don’t really have a consensus on much of econometrics and monetary policy. Macroeconomics is a contentious field, and you’ll hear all sorts of takes on the deficit and inflation — either it’s a fiscal disaster or just an accounting identity. Some of these takes are more political spin than science.

That’s why it’s important to cut through the noise and pay attention to the “real economy” — that is, stuff. At the end of the day, our monetary system is a way to coordinate and allocate the movement of stuff. You can make money at your job, but the government can also just give you money to give you legal authorization to buy stuff. And it can print money and buy stuff itself — like bombs, tanks and personal protective equipment.

Right now, the deficit is so big because the government expanded the money supply to keep stuff moving during the lockdown — and because progressives took a political opportunity to massively expand the social safety net. Contrary to popular belief, most of this is just “borrowed” from our own central bank, not China. (For what it’s worth, the “debt” we owe to China is simply a byproduct of our trade deficit. As long as they have a bunch of dollars, it’s rational for them to trade them for treasury bonds.)

How big is the national debt? Incomprehensibly big, 28 trillion dollars big. But what if someone told you that it was 56 trillion, or a quadrillion? Would it substantially change how you feel about it?

The national debt as a number doesn’t matter for Americans. At the end of the day what matters is stuff. How many people are working? How much food are our farmers farming? How many meals are poor children skipping? Is your town getting an improved highway or metro? Is your little sibling learning in a trailer? How many people are skipping a dose of their prescriptions? Always stay squarely focused on the effects on people’s actual lives, not numerical abstractions by themselves.

Your life isn’t better if inflation is under 2 percent but you’re entering a weak labor market and get stuck living at home. Your community isn’t improved if the deficit is a smaller number but vaccine rollout is delayed and your neighbors eventually go bankrupt after losing their jobs with no unemployment insurance (unemployment insurance has been one of the most expensive parts of the COVID-19 response).

It would be patently false to say that inflation and the national debt can both skyrocket with no consequences in everyday life — it’s true that reckless government policy can mess up the mechanisms that make the economy work efficiently. But if someone presents a number as a problem on its own merits — all while child poverty is poised to be cut in half, the strongest economic recovery since Reagan is being projected, and we’re on track to get to full employment — be very skeptical. Ask: How does that number affect me and those I care about?

I explained all of this to my girlfriend’s parents (they’re patient people). Juicy steak settled in our stomachs. Operation Warp Speed — which added $18 billion to the debt — translated into an extremely accelerated vaccine development. My dad had just gotten his shot; in a few weeks they’d be getting theirs.

The kids down the street would be returning to school soon — and millions of other children will be lifted over the poverty line this year alone by Biden’s expanded child tax credit, set to cost $100 billion this year.

With boring abstractions like the national debt put aside, and a homemade cheesecake on the table, the conversation turned to the real stuff of life.

“Are you excited for the summer?” her mom asked us.

Oh yeah.