Spiros Protopsaltis discusses current trends and offers advice to students

BY IZZ LAMAGDELEINE, COPY CHIEF

When Spiros Protopsaltis was the deputy assistant secretary for higher education and student financial aid in the Obama administration, he helped to expand students’ access to income-based repayment. He also helped to provide students with information about picking the right college through the college scorecard and expanded regulations toward predatory schools that saddled students with student debt.

Now Protopsaltis is an associate professor at Mason, as well as the director for the Center for Education Policy and Evaluation, with much published research on the issues that college students can face in battling debt.

He believes that even as college becomes more and more expensive, it is still a decision that greatly helps students—as long as they choose the right school.

“The headline is that we have a student debt problem, and that is absolutely true,” he said.

“The thing is, though, that once you look behind the headlines and you dig into the numbers, it’s a more nuanced story.”

With a full-time credit load at Mason currently costing in-state students $4,530 per semester, plus all the other expenses that a student has to cover including housing, food, gas and many others, thousands of dollars of debt can come with graduation and a diploma.

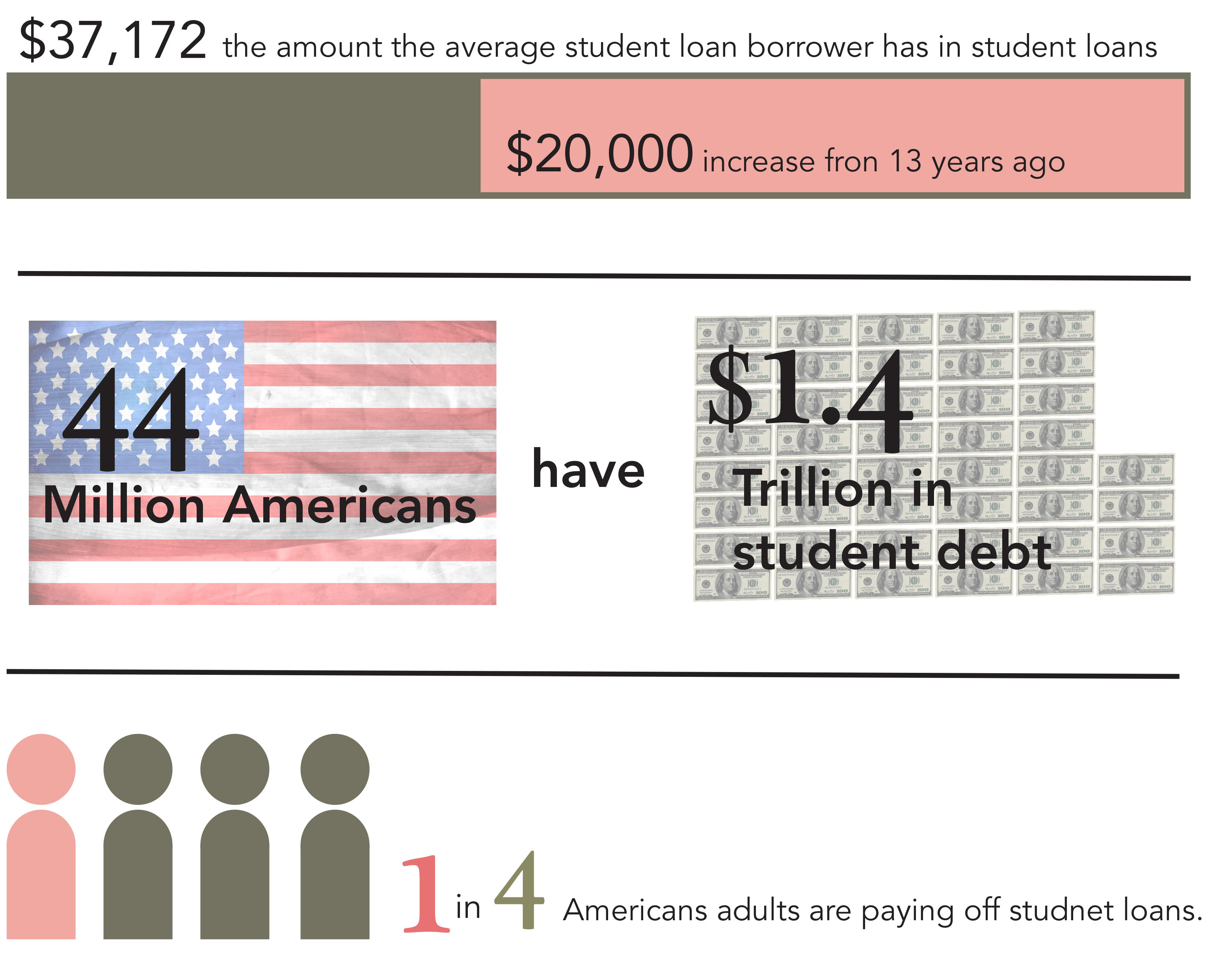

The average amount that a student owes in debt is $37,172, a $20,000 increase from the amount students borrowed in 2005, according to a CNBC article published in 2018. Roughly one-fourth of all Americans have to pay off debt that is related to their student loans.

Protopsaltis believes that students should not be afraid of the amount of debt that higher education can leave them with. As long as the debt is for an education that will give students a good future, he believes it is an investment that will help them later on in life.

An article MarketWatch published Feb. 9 mentioned that that Protopsaltis commented in a panel session hosted by the Education Writers Association about how students who drop out of college are the ones who often struggle with debt.

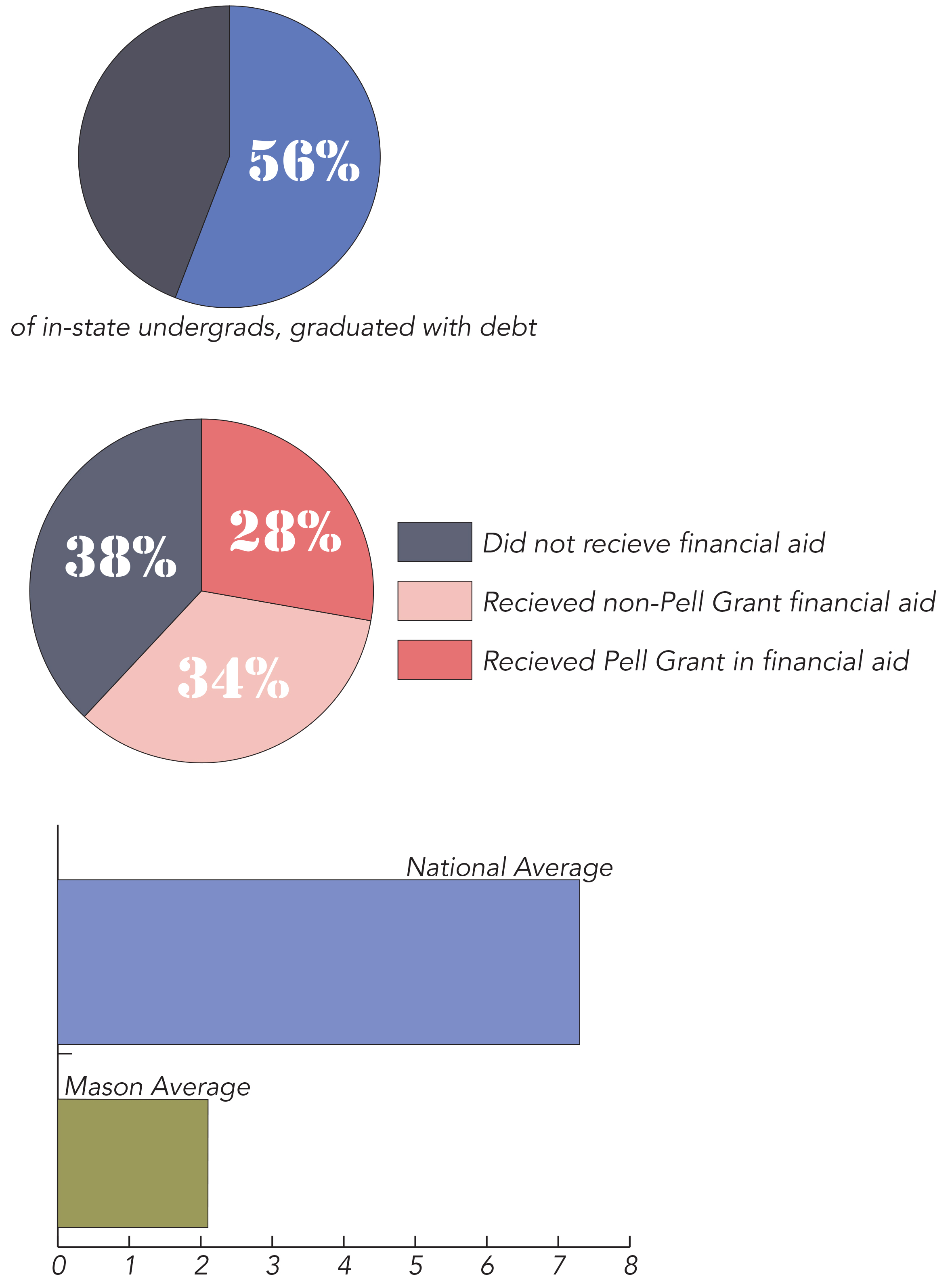

In 2016, the amount of Mason students who defaulted on their student loans was 2.1 percent. Nationwide that year, the rate was more than triple that, at 7.3 percent for four-year public institutions, according to a facts sheet made by the Office of State Government Relations Contacts.

“There is a problem with student debt because college costs are out of control, there is no doubt about that,” Protopsaltis said. “But what we don’t want to do is to scare people away from taking student loans to finance education.”

Student loans are the main way that most students can afford college. The financial aid system is moving farther away from grants and scholarships toward loans, with Forbes Magazine calculating that tens of millions of borrowers owe more than 1.5 trillion dollars in debt.

The Pell Grant, a need-based grant given to students who need it the most and described by Protopsaltis as the “bedrock of the federal financial aid system,” only gave a maximum of $6,095 per student for the 2018-2019 school year and estimates giving $6,195 for the 2019-2020 year―enough to cover only a sliver of the expenses that college students face.

“We need to strike a much better balance and make sure that grants are as available and as generous [as possible] and keeping up pace with inflation,” Protopsaltis said. In 2016, 28 percent of Mason students received support from Pell Grants.

However, the current administration appears to be going against the way of progress on issues such as the amount of funding that the Pell Grant receives, as well as the type of regulations that the U.S. Department of Education oversees. They have proposed to roll back Obama-era regulations, such as gainful employment and borrower defense. The current administration has also recommended that accreditation status be given back to the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools, which the Obama administration previously had stripped away.

“And I think that it’s very reckless,” Protopsaltis said. “I think it’s misguided, and I think that it’s very, very important to push back on this deregulation because it ignores the facts. It ignores the evidence. It fails to recognize that the problems that we’ve seen in the past … have been largely the result of deregulation that has occurred in previous administrations.”

Protopsaltis also thinks that poor-quality schools will begin aggressive marketing and recruiting, which could hurt the higher-education system as a whole.

“All the indications are that they’re going to go back to the old ways of doing things, and they’re going to continue to pursue sort of like a race to the bottom as far as I’m concerned, in terms of, ‘Charge as much as you can, and offer the cheapest education that you can in order to expand your margins and make a quick buck,” he said.

Protopsaltis advised prospective students to do their homework before picking a college to ensure that they are attending the best one for them, one that is not predatory in nature and will prevent them from ending up in debt for years to come.

When asked about students who might not have as much access to information about colleges, such as first-generation students who might have to navigate the process alone, he said that schools should start giving more information about the process earlier instead of in the latter end of high school.

As for the student-debt crisis overall, Protopsaltis believes that this is a problem that can greatly harm students and their ability to make significant financial decisions beyond college, such as buying a house.

“There are very dire consequences for students when they are unable to pay back their debt,” he said. “This is something that needs to be taken very, very seriously and has significant consequences.”