Navigating college applications as a Guyanese Indo-Caribbean student.

BY ERICA MUNISAR, NEWS EDITOR

As students apply to college, one of the most popular application mediums, Common App, offers the following race categories for students to select and identify with: ‘American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander and White’. The race option of ‘Other’ is absent. Other mediums may offer slightly deviated race selections. However, the current availability of options offered with links to affirmative action, reveal layers of further questions.

Regarding my own background, I am Guyanese, one of the most unique cultures in the world. The country of Guyana is located in South America and is considered part of the Caribbean. I am of Caribbean culture, but many Guyanese people like myself are of Indian descent and have ambiguous features due to us being brought over as indentured servants by England two centuries ago. Furthermore, Guyana is the only country in South America that is not considered Hispanic. Our documentation of ancestral roots and background were recorded and stored in a 208 year old building, the Christianburg Magistrate’s Court, which subsequently was burned down in 2011 along with any ties we may have had with ourselves to India, its villages, and the caste system.

With a unique mixture; Guyana is made up of its own Caribbean culture, soca music, fêtes, and pepperpot. Therefore, I tend to opt for the race of ‘Other’ on official forms. I do not identify myself as Asian due to our stark differences, I am not Hispanic, and I am not Afro-Caribbean which is sometimes offered as an option—though never Indo-Caribbean.

Thus, filling out college applications as a Guyanese student, I have faced hardships in picking a race category. In the many applications where I could not abstain from picking a race or choosing ‘Other’, I have had no option but to pick ‘Asian’ as my closest representation.

The results of identifying myself as Asian on official forms are consequential to my career and compromising of my identity, as many Indo-Caribbeans around the world face the same dilemmas regarding affirmative action.

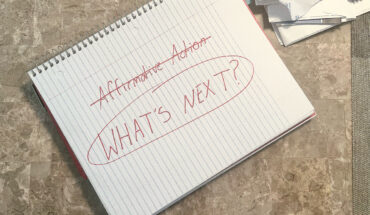

First, I must touch on the recent case of Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College. In this case, the Supreme Court may weigh banning affirmative action and their ideal aims to make college student bodies diverse by considering race as an admission factor.

According to Harvard, “If the lawsuit against Harvard succeeds, it would diminish students’ opportunities to live and learn in a diverse campus environment.” Likewise, Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) has tried to insinuate that it is unconstitutional to account for race in an application.

Understanding efforts of equity, I offer a third issue outside of political disputes subject to further scrutiny, without negation to affirmative action itself: Affirmative action is too broad to be representative.

In America, colleges consist of the two largest race groups, which are White and Asian, as described by The National Center For Education, causing colleges to give an advantage to other race groups in order to reach equity. As a Guyanese person who must identify as Asian, sources like the American Psychological Association speculate that may I face a higher proportion of competition in college admissions which could have drastic effects.

For comparison, the Census details what percentage of each race have a bachelor’s degree or higher. The results are as follows: 61.0% for the Asian population; 41.9% for the Non-Hispanic White population; 28.1% for the Black population; and 20.6% for the Hispanic population.

According to the Guyana Chronicle, in the most recent known study of 2018, only 2.3% of Guyanese people have bachelor’s degrees.

It is not uncommon within the country and culture to go straight into the workforce after grade school. However, it must be noted that Guyanese people who immigrated to America cannot be accounted for because official forms do not document our education status past Guyana itself further due to us being accounted for as only Asian. Guyanese global statistics regarding academia remain under-researched and we do not have evidence to support Asian education attainment rates at 61%.

Given the disadvantage I face, I speak to further questions that must be noted in the debate as it is not only Guyana that suffers the same disadvantage in broad applications and research. Will the Caribbean one day be accurately accounted for in future race option choices? Do Middle-Eastern persons who must identify themselves as White on official forms feel represented? Do other Asian countries with lower education attainment face their own obstacles regarding affirmative action in America?

Like my counterparts, I must continue to work harder than other groups to earn the same opportunities in academia. The Harvard case has yet to be decided, but as of now, myself and the rest of the undetected Indo-Caribbean population continue to fall through the cracks of affirmative action.