BY: ALEX MADAJIAN, STAFF WRITER

The ideas behind the Mason Core curriculum do not stand alone. They stand on the shoulders of thousands of years of the liberal arts tradition. But what is this tradition? Why does it matter now?

The “liberal” in liberal arts comes from the Latin word liber, meaning free. The ancients believed a person could become free through education. A person educated in the liberal arts was considered a master of the Trivium (grammar, rhetoric and logic) and the Quadrivium (geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy). If you had this sort of an education during the Renaissance, you were expected to be able to quote ancient Greek philosophical texts, and debate those texts in Latin.

Since the Industrial Revolution, people have wanted education to be more accessible to non-elites. Public education existed, but it was primarily concerned with the three “R”s: reading, ‘riting and ‘rithmetic.

Teaching kids born in a farming community how to act in a Shakespeare play or teaching children from factory-working families to be well-versed in French philosophy just seemed silly and unnecessary. However, with today’s economy becoming increasingly diversified, we have started to shift our focus away from strict utilitarian goals to a more sophisticated, liberally educated populace.

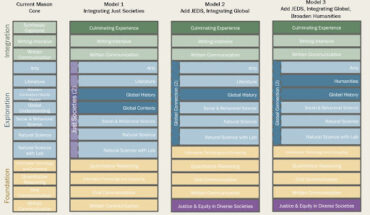

There certainly is no doubt that a broad education has advantages. But if students enter Mason solely desiring a degree in computer engineering, why would we bombard them with mandatory art history classes?

There are very few things I don’t love to learn, but I would hate every subject if I was forced to learn it. Requiring students to take classes means students will be taking them to move on, not to learn. Doesn’t that defeat the whole purpose of a general education?

Even before I came to Mason, I was taking online Ivy-league classes, learning Greek and Latin on the Duolingo app, learning advanced mathematics on Khan Academy, listening to classical books on the LibriVox app and reading them on Project Gutenberg. All of which was totally free. The only reason why I wanted to participate in those endeavors is because I was instilled by my mentors, parents and teachers with a life-long love of learning.

In a book that every student ought to read, “A Student’s Guide to Liberal Learning” by Rev. James Schall, the author lays out exactly what students really need in their education.

He writes that students should begin with two steps: self-discipline and a personal library. “Both of these together will yield that freedom which is necessary to escape academic dreariness,” he writes. But that’s not all: “Even at its best, of course, learning means we need a lot of help, even grace, but we are here talking about what we can do ourselves.”

The Mason Core Committee must do more than change the class requirements. They must foster a generation which seeks to live out a life of ideas. The best way to both honor the liberal arts tradition and adapt it to the times is to instill a culture that loves to learn on its own.

This essay is part of Fourth Estate’s special opinion section on the Mason Core curriculum from the Feb. 24, 2020 issue. Check out the lead essay here, which includes links to all the other essays.