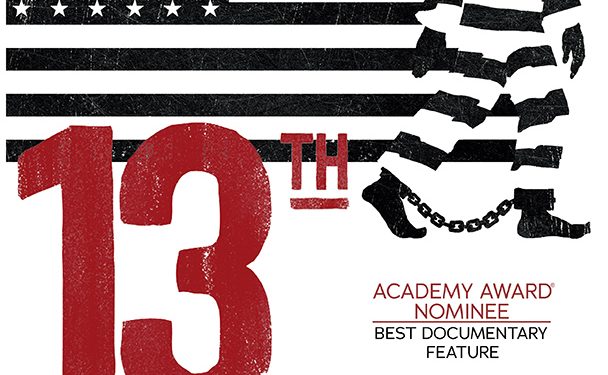

FAMS screens Oscar-nominated documentary “13th”

BY BASMA HUMADI, STAFF WRITER

Not a seat in the Johnson Center Cinema was left open. In the back of the room, audience members were left standing just to get a glimpse of the screening session.

On Feb. 13, Mason’s Film and Media Studies Department hosted a screening for the Academy Award-nominated documentary “13th” and a Q&A with Mason professor and “13th” cinematographer Hans Charles.

The screening was also a part of Mason’s celebration of Black History Month.

The documentary, which was directly released to Netflix, has generated a wide response from audiences everywhere in the United States. It explores how members of certain races in America have been exploited and manipulated since the abolition of slavery and Jim Crow laws, which enforced discrimination in the United States. Directed by Ava DuVernay, the documentary creates a critically engaging examination of mass incarceration in the United States and its relation to the 13th Amendment.

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” This “except” clause essentially created a loophole where an entirely different institution of oppression was established: the prison system. It is the conditions of the 13th Amendment which, the documentary argues, set the foundation for the current system in the United States.

Starting with the War on Drugs and leading to the Black Lives Matter movement, “13th” covers important events in black history features interviews with key intellectuals and public figures, including Angela Davis, Newt Gingrich, Van Jones, Cory Booker and Henry Louis Gates Jr.

As the cinematographer, Charles was responsible for all visual aspects of the film, such as focus and lighting. From the beginning, however, DuVernay made clear her intentions for what “13th” would not feature.

“[Ava] told me what she wasn’t going to do,” Charles said. “One of the big things I asked her — and she said she wasn’t going to do — was that we weren’t going to shoot in prisons. We won’t physically bring a camera to any prisons.”

Therefore, the challenge for Charles came with making each interview location look completely different. In some cases, three to five interviews would be shot a day in the same location.

“I knew that we would be shooting so many academics and policy makers and experts and activists,” Charles said. “I wanted there to be a sort of grittiness — some kind of contrast. But at the same time, I had to make sure the viewer wasn’t distracted from the lighting not or imagery not having a certain something to it.”

In preparation, Charles was assigned to create a “lookbook,” or a compilation of artwork that suggests what the film should strive for in terms of vision. Using this, Charles and DuVernay would work together to select interview locations that would evoke similar kinds of emotions and tones conveyed in the lookbook. Charles drew inspiration from the works of Bruce Davidson, an American photographer most popular for his series about ‘80s New York, specifically Harlem.

“I used to visit New York City every weekend with my parents,” Charles said. “We’d go to see their relatives and friends. So I remember what New York City looked like in the ‘80s. I have vivid memories. When I was looking at Davidson’s work, it felt like it was perfect.”

Charles was not particularly shocked while investigating the prison system in the process of making the documentary.

While in college, Charles had his own personal experience with the prison system when he and his roommate rented a car that was not under either of their names. They had asked a dormmate to rent a car for them because they were under 21.

“We wanted to go to New Orleans, and he wanted to come with us and we were like ‘no’ because he was creepy so we didn’t want [him] to go,” Charles said. “As soon as we left, he called the police and said that we stole the car.”

Charles and his roommate then had to attend court, which did not go according to plan. The dormmate attended the court case and fraudulently claimed he represented the university they were attending. It was a different judge who handled the case, and Charles and his roommate were thrown in jail that day. Eventually they were released, but Charles never forgot the experience.

“He ended up going to jail because, you know, he lied to the court,” Charles said. “But we still had this three-year period where we had this on our records. I kinda never forgot what that environment was like — you know, like, 60 people in cells, all this stuff going on. There was a guy that was in there for axing somebody 70 times. Insane. I never forgot that. I never forgot that experience.”

Part of the reason Charles got the job as cinematographer was that he was at the right place at the right time.

“This is sort of a fluke. I just happened to be studying the prison industrial complex, it was interesting to me,” Charles said.

Charles happened to be in Selma one day and met Van Jones at the airport there. Later, Charles went to a party Jones and DuVernay were attending. Just as DuVernay was about to introduce herself to Jones, Charles intercepted.

“Before [Ava] can even saying anything to Van to introduce me, I’m like, ‘Hey Van, wassup man! I haven’t seen you,’” Charles said. “And she’s like, ‘You know Van Jones?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, yeah, you know, we know,’ cause I’m a little bit Hollywood.”

The three then sat down and began talking about the prison system, with Charles doing his best to make an impression on the two of them.

“I kept chiming in like, ‘You know the Koch brothers, they’re doing this and that,’” Charles said.

“And they’re both like ‘Yeah, that’s right!’ So [Van] and I start talking about policy. And [Ava’s] just kind of sitting like, ‘Wow, how do you know all this stuff about this subject?’ So, really, two weeks later she called me and asked me [to be a part of the film].”

The documentary ends with a powerful quote by Bryan Stevenson, a lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative.

“People say all the time, ‘Well, I don’t understand how people could have tolerated slavery?’” he says.

“‘How could they have made peace with that? How could people have gone to a lynching and participated in that? That’s so crazy, if I was living at that time I would never have tolerated anything like that.’ And the truth is we are living in this time, and we are tolerating it.”