Highlighting an overlooked civil rights pillar

BY KARLOS CORIA, STAFF WRITER

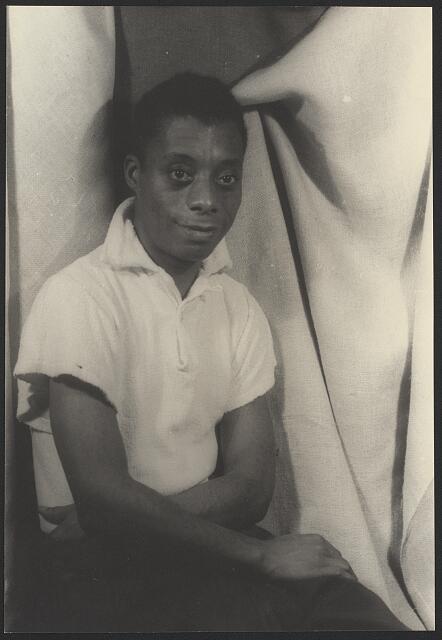

James Baldwin was set to speak before Martin Luther King Jr. at the historic March on Washington in 1963. However, the organizers barred him, saying he would be “too inflammatory.” Silenced that day, Baldwin was set to fade from America’s memory, another person disappearing into the nation’s “shadow history.”

During Black History Month, the importance of highlighting the voices of the oppressed is critical, to not only ensure that James Baldwin’s legacy is preserved but elevated.

Baldwin was an American activist, writer and an openly gay Black man. His essays and novels explored issues of race, gender, sexuality and love. In his time, Baldwin was widely recognized as one of America’s chief civil rights leaders, despite spending much of his life writing in Europe.

However, unlike Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, Baldwin is rarely mentioned in the American public education system. When learning about the civil rights movement, his work is often disregarded.

“Baldwin was unflinching in his criticism,” said Keith Clark, English and African American Studies professor and Baldwin scholar at Mason. Baldwin’s willingness to confront uncomfortable truths is one reason his work is often overlooked in mainstream discussions of the Civil Rights Movement.

While his influence waned in the years following his death, his legacy has experienced a resurgence in recent years. Clark said that this revival is due to Baldwin’s sharp critique of America’s racial and social fabric.

“In death, he is celebrated as a gay icon. But Baldwin never saw himself as a member of a queer movement,” Clark said. “It’s only been long since his death that people have tried to categorize him in that way.” The development can be credited to the themes in Baldwin’s novel, “Giovanni’s Room,” on gay love and existence, becoming a widely accepted topic of societal discussion.

For Clark, Baldwin’s importance to Black history—and American history in general—cannot be overstated.

“There needs to be Black History Month, and there also needs to be White History Month,” Clark said. “We need to always educate ourselves about our history, no matter what our race is. Baldwin was an important gender theorist and an important sexual theorist. We can’t fragment those things. Black history, like American history, needs to be recognized 365 days a year, 24/7.”

Baldwin’s critiques of race, religion and sexuality also challenge dominant historical narratives. According to Clark, Baldwin was particularly critical of the white Christian church, arguing that it was often more focused on worshipping whiteness than upholding the core tenets of Christianity.

“Baldwin’s critique of the so-called white Christian church was that [the church] was not always rooted in the King James Bible,” Clark said. “It was rooted in deifying whiteness—holding being white as sacred and upholding whiteness as sacred. Religion, for the purpose of legitimizing and concretizing hierarchies, is a bastardization of Christianity. The message of love was being perverted.”

Clark believes Baldwin’s work is relevant now more than ever, particularly in an era marked by political and social turmoil.

“America is insistent on being innocent. Part of the thrust of what we have today is people looking backward and wanting a mythic version of America that never existed,” Clark said.

When considering Baldwin’s legacy, Clark emphasized that the central theme of his work was love—though not in the superficial, romanticized sense. “The sanctity of love,” Clark said. “Not the American infantile idea of love, but the tough work of love—loving people you have been conditioned not to love.”

Baldwin’s words and ideas continue to challenge, provoke and inspire. In a time when America is still grappling with race, identity and justice, his voice remains as vital as ever.

In his prophetic work, “The Fire Next Time,” Baldwin stated that America must truly confront its history to move forward. He warns that should the country fail to do so, violent consequences will follow—but this is not the only possible outcome. Baldwin argues that ultimately, love is “the” key to overcoming the country’s obstacles. “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within,” he said.

Clark also emphasized Baldwin’s belief that love and resistance were intertwined, a theme that remains central to his legacy. “We can return to Baldwin’s essays,” he said. “Baldwin’s work was always about love, but also about resistance. In resistance, there will be suffering.”

Baldwin’s admiration for civil rights leaders like MLK Jr. and Medgar Evers was rooted in their commitment to action, not just rhetoric.

“Baldwin loved MLK, Medgar Evers. He loved these people because they did not just talk the talk, they walked the walk—and they paid for it with their lives,” Clark said. “We always crave safety, but for real change to exist, we have to give it up.”

This call to action, Clark noted, is what makes Baldwin’s work so relevant today, particularly for younger generations.

“If we were to have any hope, it would have to be in the young people,” he said.