BY SAVANNAH MARTINCIC

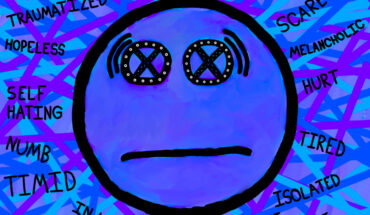

In the wake of years of mass shootings, mental illness has become a frequent topic of discussion. However, mental health care in America remains a system that does not meet the needs of some 47.6 million people who experience mental illness in any given year.

More than 10 million Americans have an unmet need for mental health care, a number that has not decreased in the last decade, and over 70 percent of youth with major depression are in need of treatment.

Those with mental illness have fallen victim to a historically broken mental health care system.

In the decades after deinstitutionalization in 1955, millions of mentally ill Americans were left behind, as state governments and counties were unwilling to pay for extensive networks of clinics.

Then, President Reagan’s 1981 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Bill raised defense spending while slashing funding to domestic programs, including federal funding for state community mental health centers.

And, with recent cuts to Medicaid, financial problems have only been further exacerbated for those seeking mental health care. An estimated 40 percent of recipients of Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act have mental health issues and could soon lose coverage.

“We have had decades of cuts in mental health treatment,” said Susan Mizner, director of the disability rights program at the American Civil Liberties Union in an interview. “We need to get to a level of being able to meet the need.

Due to the overwhelming financial burden of mental health care, many suffering from mental illness cannot pursue treatment.

The National Institute of Mental Health reports that less than 50 percent of people with mental illness received treatment in 2017; these people who sought out treatment were not in clinics or seeing a psychiatrist, but were sitting in emergency rooms waiting for treatment thanks to budget cuts and bogus insurance policies.

During the recession, states cut $1.8 billion from their mental health budgets, with the biggest cuts being made to long-term, in-patient care facilities. This has had a serious impact on hospitals’ abilities to care for mentally ill patients.

When a patient seeks in-patient care at the psychiatric ward of a hospital, they frequently have to go through the ER and then through triage — where staff are more prepared to deal with physical trauma over mental trauma. This long admissions process forces individuals in crisis to repeat their stories over and over again, until finally they are admitted to in-patient care.

But the pain does not stop there. The patient then can be detained for hours — and possibly days or weeks — in the hospital as they await their assignment to a mental health care facility for out-patient care, with some being eventually placed in overcrowded and understaffed clinics.

This dangerous practice is called “psychiatric boarding” and is often the only option for ER staff who cannot turn away mentally ill patients, but cannot find room in nearby clinics. This leads to a lack of consistent and beneficial treatment and is putting the mentally ill at severe risk in more ways than one.

According to a study by the Treatment Advocacy Center, people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter than other people approached or stopped by law enforcement. The study also reports that while individuals with untreated severe mental illness number fewer than one in 50 adults, they are involved in at least one in four and at most half of all fatal police shootings.

“By dismantling the mental illness treatment system, we have turned mental health crisis from a medical issue into a police matter,” said John Snook, executive director and a co-author of the study.

The mentally ill as a whole are overrepresented in all aspects of the criminal justice system.

At least a fifth of all prisoners in the U.S. have a mental illness of some kind, and between 25 and 40 percent of mentally ill people will be incarcerated at some point in their lives.

The broken mental health care system has created a pipeline from the streets to the “big house.” Instead of helping to treat individuals suffering from mental illness, the country finds it easier to criminalize their very existence.

To put the overwhelming number of mentally ill individuals currently in prison, consider this: 1.2 million individuals living with mental illness sit in jail and prison each year.

That is enough to fill Madison Square Garden 60 times.

Mentally ill inmates may also experience prolonged delays for services due to lack of funding, making them more likely to remain in prison longer than other inmates. Not only is this extremely unfortunate for the individual, but it also is financially straining the budget of the states.

Politicians, however, only want to talk about mental illness after a shooting. If they were actually serious about treating mental health, they would be passing policy to fix our broken mental health care system, rather than just using it to curb the gun control conversation.