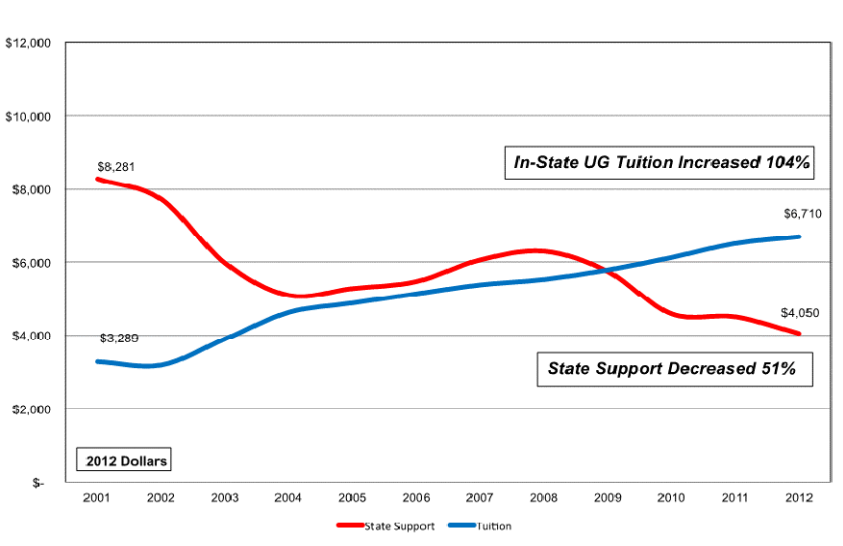

As Mason continues to grow, Virginia has decreased its contribution to the university, which push tuition prices up. (Photo courtesy of Mason’s Office of Budget and Planning.)

In a blog post last week, President Ángel Cabrera wrote about the changing relationship between public universities and the states that finance them. Cabrera presents some figures that show declining state support for universities who have had to find sources of revenue to make up the difference.

“While the collective finger these days tends to be pointed at colleges in trying to explain the ever rising tuition trends, the truth is that we, as a society, have decided to gradually shift public funding from higher education to other priorities, thus turning what we once considered as mostly a public good into a somewhat subsidized yet mostly private good,” Cabrera wrote.

As I’ve written before, the problem is not just that elected officials have reduced funding for higher education. Public institutions are now fighting over a shrinking amount of resources that are consuming state budgets, such as the rising costs pension funds, Medicare and Medicaid.

While state support is decreasing, there is increasing pressure for public universities to increase enrollment.

In 2011, the General Assembly passed the Higher Education Opportunity Act, which was meant to overhaul the state funding formula by holding public universities to a new set of performance measures. One of the bill’s more ambitious goals is to produce 100,000 cumulative additional undergraduate degrees in Virginia by 2025; a goal that would put additional pressure on schools to increase enrollment.

There may, however, be contention between promoting institutional flexibility and aligning university visions with state goals.

Mason is a growing institution that seems to primarily shape itself around providing an accessible (both logistically and financially) education. Even recently, the Washington Post reported that traditional four-year college students are becoming scarcer. Students who juggle part-time jobs, families and other obligations are increasingly filling the classroom. These are precisely the type of students that Mason seeks to support.

But that’s also the problem with how the state allocates funding. From what I understand, the state rewards performance standards that are more supportive of low-acceptance rate institutions who still operate on the traditional four-year undergraduate model. Mason’s four-year graduation rate is only 42 percent, and most of that has to do with the fact that we’re highly flexible in terms of part-time and professional students. So while Mason increases enrollment and supports a greater number of students, the funding doesn’t follow to help reach those goals.

How will the state’s funding model support the different visions of schools like Mason to those like the College of William & Mary?

To make matters more complicated, the state has given a great deal of autonomy to public Board of Visitors when it comes to the direction of the universities.

According to a report released by the research arm of the Virginia General Assembly, state Board of Visitors have more autonomy today than at any other time in history. In fact, Virginia as a whole has one of the most decentralized higher education systems in the state.

That’s certainly not a bad thing. Virginia’s system is often praised for having a diverse set of institutions that include small liberal arts colleges like Mary Washington, while also supporting larger technical schools like Virginia Tech. It may, however, make it more difficult for public universities to align their visions with the state and with each other.