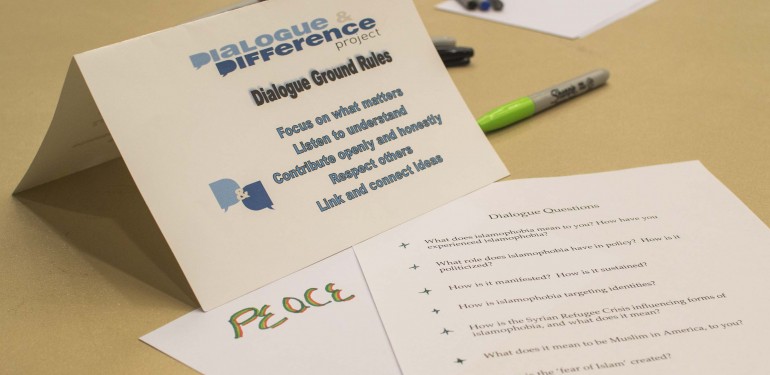

(Photo credit: Alya Nowilaty/Fourth Estate)

As part of the Dialogue and Discussion Project, the Mason community came together last Tuesday night to discuss Islamophobia.

The evening started with each of three panelists giving a short presentation.

Remaz Abdelgader, a senior conflict analysis and resolution major and student activist, began by sharing the personal impact Islamophobia has had on her life. She expressed “the subtle discrimination” she experienced on a daily basis, and then narrated an overtly Islamophobic experience that took place during her second year at Northern Virginia Community College.

“This happened after I had just left an evening biology class in community college. ‘Move out of the way you terrorist,’ he screamed at me as only inches separated my physical body with his car. The force jolted me and I threw myself back. As his car came to a screeching halt, the stranger rolled down his window completely and stuck his head out to stare. I was stunned at what had just occurred, I looked on with fear into the stranger’s eyes fearing that he might just shoot me, as he went on to say the following:

‘This isn’t Iraq bitch. I hate you Muslims, you’re lucky I don’t kill you,’” Abdelgader said.

Abdelgader continued to explain that the American Muslim community has experienced, and is continuing to experience, the first six out of ten stages of genocide, according to Gregory Stanton, founder of Genocide Watch and professor of Conflict Analysis and Resolution.

Abdelgader added that the institutionalization of xenophobia, which is the dislike or fear of people from other countries, and discriminatory policies perpetuates and mobilizes hate, while inducing fear.

“Fear allows us to be accepting of conformity and oppression, fear erodes the foundation of democracy, and fear kills freedom,” Abdelgader said.

Next, Nathan Lean, author of “The Islamophobia Industry,” explained that Islamophobia exists on two levels. We experience, confront and interact with Islamophobia on the micro level. While Islamophobia on the macro level not only includes prejudice within the workplace, community, schools, neighborhoods and so on, it is also fixed to larger power structures “that are fairly intractable,” Lean said. “It’s institutionalized in a way that makes dealing with it very difficult.”

According to Lean, the problem with addressing prejudice that exists at both levels is that even if progress is made on the micro level, much progress will still need to be made on the macro one. Unlike other institutionalized prejudices, however, Islamophobia is fastened to American foreign policy in regards to Muslim-majority countries, predominantly ones in the Middle East.

“There is this foreign policy apparatus that drives so much of this phenomenon, and really drives and animates what we see and experience at the micro level,” Lean said.

In order to address Islamophobia at the macro level, Lean believes that a “robust critique of foreign policy” is essential. This involves “uncomfortable but necessary conversations and dialogues” on a variety of issues from drone attacks to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Moreover, there is this “drift towards a state of perpetual warfare” that needs to be re-evaluated.

America’s foreign policy as it currently is creates a climate where Islam is filtered to us as news, according to Lean. For a number of Americans, the only familiarity they have with the religion of Islam is within the context of explosions or terror attacks leading to a misrepresentation of Muslims as “only engaged in conflict.”

Lean then touched on the Foreign Enemy Domestic Threat, which is the way in which learning abut an enemy abroad, such as an Islamic extremist group, can cause people in the United States to perceive a threat among Muslims at home. The belief in a threat at home then results in the implementation of discriminatory policies.

“Violence isn’t necessarily confined by a particular geographic border, it’s not confined by space, it’s not confined by time, but violence plays out in places like Iraq and Syria [and] is refracted really through a prism in which Muslims here in the United States and Europe are viewed through that violence. It leads to all sorts of institutionalized policies,” Lean said.

The third panelist, Mobeen Vaid, a Mason alumnus and a chaplain for the Well Muslim Fellowship at Mason, touched on Islamophobia within various forms of media, including the news, television and video games. He said that Islamophobia is no longer an exclusively Western problem, but is “becoming a global phenomenon,” an example of which is India.

Among the institutionalized policies previously mentioned by Lean is the surveillance of Muslims.

“Many, many Muslims in this area … have had the FBI visit their homes,” Vaid said

Vaid added that Muslims are aware that they are under a microscope, and as a result self-domestication occurs. There is a need for Muslims to constantly prove how American they are.

According to Vaid, an important distinction when talking about American Muslims within the Muslim discourse is recognizing ‘American’ as a value predicate rather than a geographic predicate. Instead of hearing “American” and thinking of a location, it should be seen as a modifier that conveys specific cultural context — like principles or values. Therefore, American Muslims will modify their own beliefs and values to better conform with typical American beliefs, Vaid said.

“The dialogues that occur between Muslims and non-Muslims often occur in the form of cross-examination and not as a conversation between peers,” Vaid said.

After the panelists’ presentations, the audience asked questions.

In response to a question about the personal impact Islamophobia has on Muslims, Vaid responded, “there’s a fear of being too Muslim.”

He explained that children that are active in their communities are told by their parents to moderate the frequency they attend mosque, because you may fall under suspicion if you are too active as a Muslim. Additionally, parents will give children ambiguous names that are not easily recognized as Muslim, as a result of the environment that exists.

Abdelgadar added that she has friends that are hesitant to wear their headscarves, and in the past month has had three remove their headscarves.

In response to a question about explaining Islam to those unwilling to listen, Lean answered, “it’s important for non-Muslims to see their Muslim colleagues as not necessarily Muslims first, but as people first … we tend to see other religious groups in their diversity, and in their full humanity that I don’t think we see with Muslims.”