This story was originally published in the April 20 print issue.

As Mason adapts to the growing demand for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) education, other departments are examining the role of technology as a tool of learning and teaching.

Mason’s concern for STEM echoes a national demand. At the end of March, President Obama and the White House announced over $240 million in funding toward increasing the availability, capability and reach of STEM courses to students and especially underserved demographics. Though the initiative is funded by the private sector, it signifies an organized, top-down push for expanded and improved STEM education. STEM has become an educational buzzword as the U.S. grapples with a middling global performance. In February, the Pew Research Center reported the U.S. ranks 35th of 64 in global math scores, with Singapore in 1st.

As for college students, the White House March press release stated “Sixty percent of students who arrive at college intending to major in STEM subjects switch to other subjects, often in their first year.”

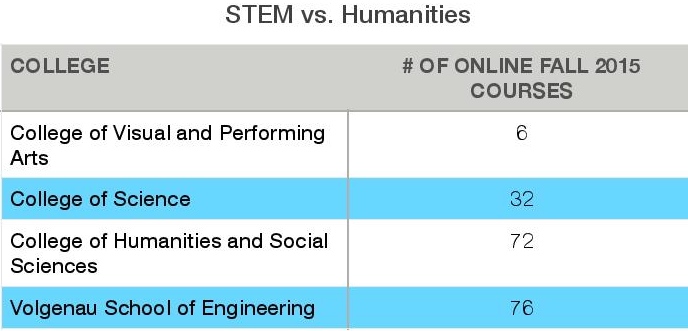

Mason has instituted an award-winning STEM accelerator program to increase the number of students within the College of Science and boost job-placement assistance for graduating students. Mason’s steps to improve STEM programs include distance education, where STEM courses are the majority of classes offered. However, other departments are utilizing technology and distanced learning to offer students convenient and modern outlets for learning.

Even as Mason wrestles with national education concerns, it is the humanities department that is bucking trends. This summer at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, graduate students will have the opportunity to explore the developing link between distanced-learning, technology and history. The course, titled Teaching Hidden History is aimed at promoting technology as a means of creating new ways of learning. It also incorporates traditional teaching of history through artifacts.

PhD student Celeste Sharp will teach the class alongside fellow PhD student Nate Sleeter. Sharp explained, “Basically this course grows out of a previous online course that we’ve done with teachers entitled Hidden in Plain Sight.”

Sleeter demonstrated the type of learning in Hidden in Plain Sight, “[Students] see an object like a porcelain teacup and they’re asked to make a hypothesis about ‘how might this object fit into a larger history. They write down that hypothesis and they go through a series of resources.”

Sleeter pointed out their thinking after the initial Hidden course, “We decided if we want to encourage this active thinking about the past. It would be great to have a course where the people in the course could actually make one of these modules: figure out what object they want to use, what story they want to tell and then implement it into a website we’ve created.”

Though focus on the sciences is aided by the advent of new technology, humanities courses have not embraced it as quickly. However, Sleeter is not convinced that history has nothing to offer to emerging trends in distance learning.

“What humanities is good at is taking a lot of information and trying to find meaning out of it. So there is a really symbiotic relationship between the two that’s exciting to explore,” Sleeter said.

“There’s a lot of people doing really exciting work in the digital humanities and digital history, but they’re probably in the minority as well. It’s not hard to imagine that people that get interested in history are the ones who aren’t going to look to technology first and say, ‘Oh, I can do this digitally,’ or, ‘Oh, I want to explore what’s possible in digital areas,’” Sleeter said.

Teaching Hidden History is one of Mason’s available hybrid courses. These classes incorporate the convenience of online learning with face-to-face time. These classes rely on multimedia telepresence rooms. The purpose of hybrid courses is to foster self-motivated study online while “the in-person allows us to do a lot of instruction in terms of the technology” Sleeter said.

The course is being funded by 4-VA, an initiative that pulls Virginia schools together to explore “collaborative research.” So far 4-VA includes five schools: Mason, Virginia Tech, Old Dominion, James Madison and University of Virginia. Though this pilot course will only involve Mason and Virginia Tech, further courses could include other 4-VA schools.

Working together across campuses can allow for a thematic focus. Sharpe pointed out, “For instance, there might be somebody at Virginia Tech who specializes in, say, the history of slavery. So you could do a version of this that’s focused thematically and content-wise on the history of slavery.”

On the role of digital history at Mason, Professor Kelly Schrum, Director of Educational Projects for the Center of History and New Media, spoke optimistically, “It’s definitely a growing field, and I think here at Mason digital history has been central for a long time. So I think our doctoral students are at the cutting edge of what’s happening.”

Digital history is only one way in which humanities and technology represent a mutually beneficial relationship. The course is developing the path for future exploration.

Schrum concluded, “In a sense we’re helping to shape the field and to change it and to increasingly find new ways and promote new ways to think about how digital and technology and humanities work together…we’ve seen tremendous growth over the last twenty years ongoing.”

Graphic Credit: Ellen Glickman

Photo Credit: Amy Rose