BY: ALEX MADAJIAN, STAFF WRITER

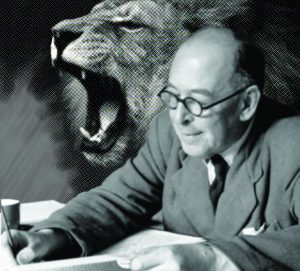

Few know the power of stories, fewer still know the beauty of fairy-tales, and almost no one knows the truth of myths. Perhaps that is why C.S. Lewis was one of the greatest authors of the 20th century.

You may remember him for writing “The Chronicles of Narnia.” Although it is a wonderful series, there is so much beyond the pages and within the man you may not have noticed. Very few realize he may have been the greatest light of joy and hope in the fight against the darkness of pain and despair.

The literature of Lewis’ day, such as “All Quiet on the Western Front,” “The Stranger” or “The Catcher in the Rye,” focused on displaying the world as a dank, dark, pointless and usually depressing reality.

Lewis had something the world had forgotten: hope. He reminded the world to see everything through the eyes of a child with stories.

Clive Staples Lewis hated his name probably as much as you do. In fact, he disliked it so much, by the age of five he insisted everyone refer to him as “Jack.” Jack was no stranger to pain. When he was 10, his mother died of cancer, and after only a few weeks, he left his home to go to a boarding school with a literally insane headmaster. Anyone who reads “A Grief Observed” knows the raw anguish his soul experienced when his wife of less than four years tragically died of cancer.

Although many remember Lewis as a Christian, many forget he was an atheist throughout his teens and 20s. Although, he was very conflicted. In reflection on this period, he said, “I maintained that God did not exist. I was also very angry with God for not existing.”

His spiritual transformation was not overnight. Several influences of the course of his life shaped his thinking, even after he rejected atheism. One major factor was George MacDonald’s “Phantastes.” He said it “baptized” his imagination, probably because of MacDonald’s use of fairy tales to demonstrate a Christian message.

The other major factor was a personal friend of his you may know of: J.R.R. Tolkien, the author of “The Lord of the Rings.” Lewis and Tolkien were both part of a literary society called the Inklings. Each would bring drafts of what they were working on, then constructively criticize each other.

Through this group, he created some of his finest works. One of his first successes was is space trilogy, with the first book being “Out of the Silent Planet,” in which the main character — a philologist modeled after his friend Tolkien — investigates God’s relationship with man and the alien species of other planets, and how that relates to us as humans.

The most well-known example would be “The Chronicles of Narnia.” I’ve read through te entire series three times, and I still get something out of it. The first published book is a direct allegory to the Christian Gospel, with Aslan representing Jesus, the White Witch as the Devil and Edmond as humanity.

Although he does write many magnificent nonfictional philosophical works, such as “Mere Christianity” and “The Problem of Pain,” they don’t carry as much weight to a non-Christian audience. He understood the power of fairy tales. But he also understood that people needed time to grow up into children again.

Wait, grow up into children?

Yes. As Lewis wrote in his dedication in “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe,” to his goddaughter, “I wrote this story for you, but when I began it I had not realised that girls grow quicker than books. … Someday you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again.”

As another of Lewis’ influences, G. K. Chesterton, put it: “Fairy tales do not tell children the dragons exist. Children already know that … Fairy tales tell children the dragons can be killed.” No one reminded us better than Lewis that we are meant to be dragon slayers.