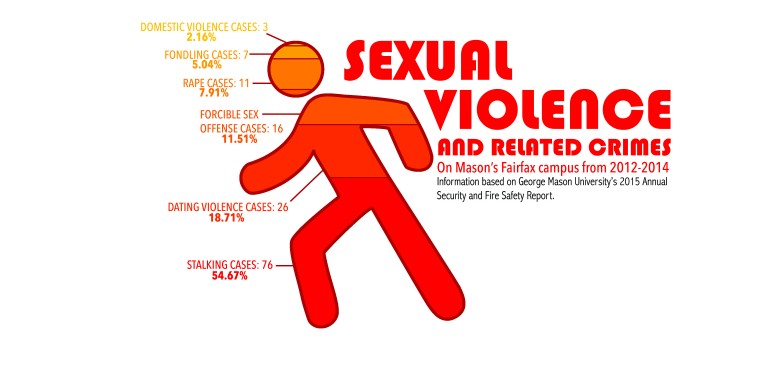

(Credit: Megan Zendek/Fourth Estate)

This year’s Annual Security and Fire Safety Report contains more information concerning sexual assault than previous reports, mostly due to changes to the Clery Act. The federal Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act contains requirements for how universities deal with cases of sexual and domestic violence and includes reporting obligations related to these crimes.

The 2015 report is 82 pages longer than the 2014 report. Of those additional 82 pages, approximately 41 contain information related to sexual violence that was not included in last years’s report.

The majority of new sections are reference documents, including a list of programs Mason provides to prevent sexual assault and descriptions of bystander intervention, among others. In total, there are approximately eleven sections that cover sexual assault in some way.

Recent amendments to the Clery Act mandated the reporting of this information, which also includes many legal definitions of sexual assault and related criminal activity. In 2013, the Clery Act was expanded to include the Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act, which “increases transparency on campus about incidents of sexual violence, guarantees victims enhanced rights, sets standards for disciplinary proceedings, and requires campus-wide prevention education programs,” according to KnowYourIX.org. This act is partially responsible for the new information included in Mason’s annual report.

“All these new things have to be disclosed,” Thomas Longo, Mason’s interim chief of police, said. “The policies have to be disclosed, and those are naturally somewhat legalistic in their wording, and they’re long.”

Among the new Clery requirements is more detailed reporting on sexual violence from Campus Security Authorities (CSAs). Before the amendments were passed in 2013, CSAs only had to document whether the incident was a forcible or non-forcible sex offense. Now CSAs must document what kind of forcible sex offense occurred. As a result, the number of rapes and fondlings that were reported in 2014 are included in this annual report.

One of the additional sections is called “Sexual Assault, Dating Violence, Domestic Violence, and Stalking Laws in Applicable Jurisdictions.” It includes how the state of Virginia defines various crimes related to the listed categories. This part of the report includes Virginia’s definitions of crimes such as rape, aggravated sexual battery and stalking, among others. It also contains the state’s definition of terms related to these crimes such as “complaining witness” and “sexual abuse.”

Longo said this is important information because what can be prosecuted as sexual violence can sometimes be different from the cases of sexual violence the university is required to report under the Clery Act.

“Some of those definitions differ,” Longo said. “So, for example, the legal definition of a rape or a forcible fondling, or something like that, may be different in some cases from the Clery definition.”

Another new section, “Procedures Victims Should Follow in Cases of Sexual Violence,” lists steps for survivors to follow depending on their situation. For example, there are instructions if an assault recently occurred or if it happened a longer time ago. There are also steps to follow in the cases of stalking and domestic violence. This section also provides details of undergoing a post-assault medical exam.

Longo said the new information will enable survivors of assault to find the help they need.

“I think the information is empowering,” Longo said. “… It’s empowering personally because you know, first off, what your rights are. You know there’s a support structure there so you don’t just have to quietly endure something that happens to you that’s wrong.”

One helpful aspect of the report, Longo said, is that it contains all the options for survivors of assault.

“For example, let’s say I was a victim of a rape, and I’m very traumatized about it,” Longo said. “I don’t know if I want to go through it again in court; I don’t know if I want to tell my story to police officers. I can look at this safety guide, and I can see that I can go to other sources that will treat it confidentially, and they will help me and give me the support that I need. But I don’t have to go through all this other stuff unless I decided, ultimately, that I want to. That’s empowering.”

Longo said the information in the annual reports helps Mason Police maintain its essential purpose.

“Ultimately, what we exist for is to keep students such as yourself focused on what they came here to do, and that is to get their degree and to be a success in life,” Longo said.

According to Longo, how campus police departments handle sexual violence has changed throughout the years.

“This is a paradigm shift from when I started in this business 30 years ago,” Longo said.

He said he has seen programs and initiatives concerning the Clery Act, Title IX and sexual assault escalate, particularly in the past five years.

“It was a thing which we basically report on every year, but it wasn’t nearly as proactive as it is now,” Longo said.

He said this shift within police departments and universities has potentially led to an increase in victims reporting.

“I think there’s an awareness now not only of the Clery-type things, but that I [a victim of sexual violence] can tell someone about this, and I can do it confidentially, or I can do it more out in the open and prosecute if I want,” Longo said. “I think people are feeling more empowered.”

To view the entire report, which includes emergency and evacuation procedures, crime prevention programs and fire safety tips and statistics, among other safety information, visit the Mason Police website at police.gmu.edu or stop by Police and Public Safety headquarters to pick up a hard copy.